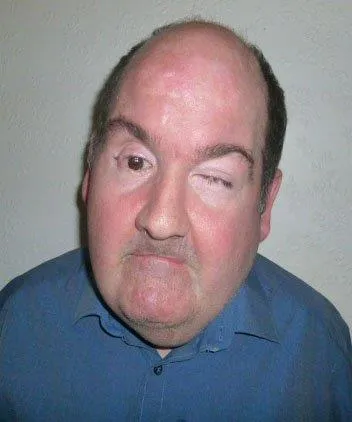

Chris Cook

Diagnosed with diabetes in summer 2007 at the age of 33

Accessibility should be everyone’s responsibility and I strongly feel that when it comes to making our world more accessible for all, doing nothing is not an option.

Chris, a disability awareness trainer and accessibility consultant, lost all useful vision at the age of 8 due to a combination of an extremely rare medical condition and a seemingly routine case of conjunctivitis. He contacted us to tell us what kind of things we could do to make our website more usable for people with visual impairments.