Key messages

- This chapter focuses mainly on fear of hypoglycaemia. Other diabetes-specific fears (worries about complications, and fear of hyperglycaemia and needles) are briefly described. Fear of hypoglycaemia refers to extreme fear that impacts on quality of life and diabetes outcomes, which differs from an appropriate level of concern about hypoglycaemia.

- Fear of hypoglycaemia is a specific and extreme fear evoked by the risk and/or occurrence of low blood glucose levels.

- Fear of hypoglycaemia affects one in seven people with type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes. These fears can also affect family members.

- Fear of hypoglycaemia is associated with impaired quality of life and emotional well-being, sub-optimal diabetes self-management and HbA1c, and more diabetes-related complications and symptoms.

- The Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey-II Worry scale (HFS-II W) is useful for assessing fear of hypoglycaemia and to guide conversations about fears.

- Psycho-educational interventions are effective for reducing fear of hypoglycaemia.

- People with diabetes and their families often have limited knowledge about hypoglycaemia beyond ‘survival skills’, which may lead to fear of hypoglycaemia.

- People with diabetes may also experience other types of diabetes-specific fears, including fear of hyperglycaemia, diabetes-related complications, and injections/needles.

Practice points

- Acknowledge that fear is a normal response to a threat (e.g. hypoglycaemia) and that a certain level of fear is adaptive (e.g. keeping the person alert for symptoms or motivated for self-management), but acknowledge that extreme fear may impair the person’s well- being, self-management, health, and quality of life.

- Be aware that a person may experience extreme fear of hypoglycaemia in the absence of actual hypoglycaemia and irrespective of their HbA1c.

- Remain mindful that people may be reluctant to talk about their fear (or experience) of hypoglycaemia with a health professional (e.g. fearing loss of driver licence).

How common is fear of hypoglycaemia?

|

|

What is fear of hypoglycaemia?

Fear of hypoglycaemia is a specific and extreme fear evoked by the risk and/or occurrence of hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose). Hypoglycaemia is a side-effect of glucose-lowering medications (e.g. insulin, sulfonylureas), and caused by relative insulin excess in the absence of sufficient blood glucose.

If undetected and untreated, glucose continues to fall, resulting in severe hypoglycaemia (a very low blood glucose level, requiring the assistance of another person to treat it). Also, hypoglycaemia can lead to a ‘vicious cycle’ of recurrent hypoglycaemic episodes. Unsurprisingly, many people with diabetes worry about having hypoglycaemia. People fear losing consciousness in public, having an accident/injury, becoming emotionally upset or uncooperative, and embarrassing themselves. They also worry about the very worst (but rare) scenario, sudden death.

In adults with type 1 diabetes, fear of hypoglycaemia is more pronounced in those with a history of severe hypoglycaemiac (often complicated by loss of consciousness or hospitalisation, or affecting work, or nocturnal), or who have impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia.

In adults with type 2 diabetes, fear of hypoglycaemia is greater in those using insulin compared to those using sulfonylureas, which can also increase the risk of hypoglycaemia. As the prevalence of severe hypoglycaemia in adults with type 2 diabetes using insulin for more than five years is very similar to adults with ttype 1 diabetes, they share the same concerns about hypoglycaemia. In those using oral agents, anticipation of problematic hypoglycaemia can be a psychological barrier to insulin initiation.

Being concerned about hypoglycaemia is both rational and adaptive, as it keeps a person attentive and responsive to hypoglycaemic symptoms to enable timely and adequate treatment. However, if these concerns evolve into excessive fear, it may have a huge negative impact on the person’s quality of life and their ability to manage their diabetes. It can also affect the quality of life of family members (e.g. with sleep disturbances or worrying about the person’s safety when alone). The absence of concerns about hypoglycaemia is discussed in Box 4.1

Although the focus of this chapter is on extreme fear of hypoglycaemia, other diabetes-specific fears are discussed briefly below: fear of needles, injections and finger pricks (Box 4.2), extreme concern about hyperglycaemia (Box 4.3), and worries about long-term complications (Box 4.4).

Sometimes, the person’s level of fear is disproportionate to their actual risk of hypoglycaemia. Striving to maintain HbA1c within target while avoiding hypoglycaemia is challenging, and understandably may lead to high levels of fear of hypoglycaemia. Fear of hypoglycaemia may develop for many reasons:

- Limited understanding of hypoglycaemia and skills in preventing, recognising, and treating hypoglycaemia can cause more frequent and severe hypoglycaemia episodes, which can evoke fear of hypoglycaemia.

- Awareness of hypoglycaemic symptoms can decrease the longer a person lives with diabetes, making it more difficult for them to notice falling blood glucose levels and could lead to fear. Typically, their brain will already be lacking glucose before they recognise it. When it gets to this stage, the person’s ability to stop what they were doing and treat the low blood glucose (promptly and effectively) is severely impaired.

- Previous experience of a traumatic hypoglycaemic episode – especially one complicated by loss of consciousness or hospitalisation, or happening while asleep – can make people fear another episode. One severe hypoglycaemic event, as well as recurrent mild episodes, can trigger fear of hypoglycaemia.

- Certain personality traits, for example neuroticism (type 1 diabetes), high trait anxiety, and general fear (type 1 and type 2 diabetes), are associated with fear of hypoglycaemia; this relationship is most likely bi-directional. A person with trait anxiety may be distracted and miss out on recognising hypoglycaemic symptoms, increasing their risk of a low blood glucose level. Conversely, the experience of recurrent severe hypoglycaemia may induce fear and anxiety in people who were not previously anxious.

- The autonomic symptoms of hypoglycaemia (e.g. tremors, sweating and palpitations) are similar to anxiety symptoms. This overlap can hinder interpretation and appropriate treatment of a falling blood glucose level.

There are various ways that adults with diabetes respond to their fear:

- Some may use ‘compensatory behaviours’ to avoid hypoglycaemia and thus reduce their fear. The most common behavioural strategies include reducing insulin doses, omitting injections, or snacking continually to maintain higher blood glucose levels; this may lead to a higher HbA1c. Over time these behaviours may evolve into a habit, which makes them more difficult to identify. Reducing insulin occasionally (e.g. when attending an important meeting or giving a presentation) will not have a major impact on diabetes outcomes but it becomes problematic if the strategy is used repeatedly.

- Others cope with their fear by restricting their activities (e.g. exercise) or by avoiding being alone, which will have an impact on their independence, confidence, and spontaneity.

Fear of hypoglycaemia is associated with:

- impaired quality of life and emotional well-being

- reduced engagement with diabetes management

- impaired diabetes outcomes.

Box 4.1: An absence of fear can also be a 'problem'

People who have impaired awareness of hypoglycaemic symptoms have a six-fold higher risk of severe hypoglycaemic events.16 Qualitative studies revealed that some of these people are not concerned about their loss of awareness and, therefore, do not appear to fear hypoglycaemia. Beliefs underlying this lack of concern include:

- normalising impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia: loss of awareness and hypoglycaemia are considered ‘normal’ aspects of living with diabetes and not as a problem; indeed, some feel that regaining awareness of symptoms would be more of a problem

- minimising the consequences of impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia: they believe they function well even when their glucose level is below 3.0 mmol/L

- avoiding the ‘sick role’: not attracting attention, not making a ‘fuss’ and ‘getting on with life’ is perceived by the person with diabetes as being ‘in control of diabetes’ and not allowing diabetes to ‘infringe’ on their life

- overestimating the risk and impact of hyperglycaemia: responses emphasise significant anxiety about developing long-term complications and extreme behavioural responses to high blood glucose levels.

These beliefs and attitudes are likely to prevent people with diabetes from being motivated to regain awareness or minimise severe hypoglycaemic events. They may be reluctant to take action to prevent, detect, and promptly treat low blood glucose. This attitude can cause a significant burden on their partner or family members who are often the first to notice signs of hypoglycaemia and/or the ones who have to manage a severe hypoglycaemic event.

Box 4.2: Fear of needles, injections and finger pricks

A diagnosis of type 1 diabetes may evoke anxiety and fear of needles, injections and finger pricks. People with type 2 diabetes not using insulin may have these fears too, which can contribute to reluctance to begin using insulin. It is the fear of the unknown.

For most people, these fears lessen after they have participated in diabetes education, adjusted to the diagnosis, and acquired skills and confidence for injecting insulin and checking blood glucose. Modern insulin pens, finer needles and lancets all help to minimise the pain of insulin injections and blood glucose checks.

Needle phobia is a more extreme and debilitating form of fear. For people with a needle phobia, the sight of a needle or blood evokes anxiety and an increased heart rate, followed by a drop in blood pressure, dizziness, fainting, sweating, and nausea.

Needle phobia is rare but, if it is present, it will complicate self-management.

Fear of needles, injections or finger pricks have an impact on:

- diabetes management (e.g. by reducing the number of injections or blood glucose checks)

- diabetes outcomes (e.g. elevated HbA1c, greater risk of long-term diabetes complications)

- emotional well-being (e.g. impaired general well-being, diabetes distress).

Explore the causes of the person’s fear – this will help to inform the action plan. Strategies to reduce the fear may include: diabetes education, behavioural therapy, desensitisation or distraction, and relaxation.

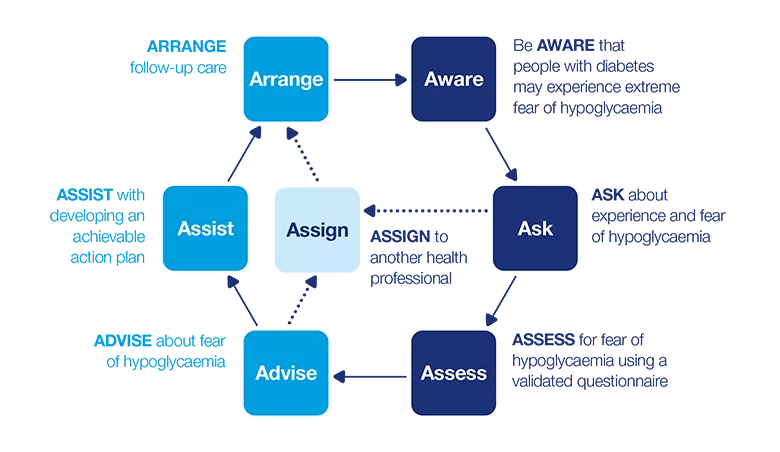

7 As model: Fear of hypoglycaemia

This dynamic model describes a seven-step process that can be applied in clinical practice. The model consists of two phases:

- How can I identify fear of hypoglycaemia?

- How can I support a person who experiences fear of hypoglycaemia?

Apply the model flexibly as part of a person-centred approach to care.

How can I identify fear of hypoglycaemia?

Be AWARE

Fear of hypoglycaemia can present itself in many ways. Some common signs to look for include:

- ‘over-compensatory behaviours’ (e.g. taking less insulin than needed or frequent snacking)

- ‘avoidance behaviours’ (e.g. limiting physical or social activities, avoiding being alone or situations in which hypoglycaemia may be more likely)

- acceptance of persistently high blood glucose levels

- excessive daily blood glucose checks

- not implementing ‘agreed’ treatment changes to lower blood glucose levels.

Although a history of hypoglycaemia is a well-established risk factor for fear of hypoglycaemia, fear can occur in the absence of actual hypoglycaemia. Perceived and actual risk of hypoglycaemia are equally likely to cause fear.

ASK

Hypoglycaemia is very common when diabetes is managed with glucose-lowering medications. Therefore it is advisable that you ask people with diabetes using these medications about their experiences of hypoglycaemia at every consultation. If this conversation reveals or the person exhibits signs that they fear hypoglycaemia, explore this further with them.

As fear of hypoglycaemia can have various causes, the following questions are examples of how to gain a better understanding of the underlying reasons.

Ask about their experiences of hypoglycaemia (hypos)

Explore frequency and severity, how they manage a hypoglycaemic episode, and their knowledge about low blood glucose. For example:

‘Have you had any hypos [in the last month/week/ since we last met]?’

- Explore the frequency, severity, time (night or day), and place (at home or elsewhere).

- Did they need help from someone to treat the hypoglycaemia?

- Did they access health services (e.g. ambulance, emergency room, hospital admission)?

‘Could you describe the symptoms you had when your blood glucose was going low?’ or ‘What do you feel when your blood glucose goes low?’

- Explore what they define as hypoglycaemia, and at what level they usually recognise symptoms.

- Explore how they identified hypoglycaemia (e.g. because of symptoms or by checking their blood glucose).

- Ask about any additional symptoms, as this process will encourage them to reflect on what exactly happened.

‘What do you think caused this hypo?’

- Explore whether they believe the cause to be due to external factors (e.g. an imbalance between food intake, insulin dose, physical activity; or heat, illness, stress, alcohol).

‘How did you react to this hypo?’

- Explore both behavioural and emotional reactions.

- Check for inappropriate behaviours (e.g. delaying treatment or using ineffective foods/drinks as ‘hypoglycaemia treatments’).

- Check for psychological barriers (e.g. feeling embarrassed or criticised when taking a sugary food/drink in the presence of others or in public places).

- Ask whether they reduced their insulin to avoid future hypoglycaemia.

‘Is there a way you could avoid a similar episode in the future?’

- Explore the extent to which the person has reflected on the causes and considered how/ what to learn from the experience.

If the person does not experience hypoglycaemia, this does not necessarily mean that they have no fear of hypoglycaemia. Ask the following questions regardless of the person’s responses above.

Ask open-ended questions to explore the level of fear of hypoglycaemia:

‘People with diabetes using [insulin/tablets (type 2 diabetes)] are sometimes concerned about their blood glucose going low. How do you feel about low blood glucose levels/hypos?’

-

If the person has few or no concerns, verify whether this is consistent with their actual risk or experience of hypoglycaemia.

- If the person is highly concerned, explore whether it impacts on their diabetes management and/or quality of life, for example:

‘What has been your worst experience with hypos?’

‘What concerns you the most about hypos?’

‘How is your life affected by hypos?’

‘Have you ever had a severe hypo in the past with unpleasant consequences for you or others? Tell me a bit more about what happened?’

‘What is the lowest blood glucose level you feel comfortable with?’ and ‘What is the highest?’

‘When you go out, what is the lowest blood glucose level you feel safe with?’

Ask directly about compensatory behaviours, in a sensitive and non-judgemental way:

-

‘Some people take less insulin because they are worried about having a hypo. Are there times you (ever) reduce your insulin to avoid hypos?’

-

‘Some people keep their blood glucose at a higher level to avoid hypos. Are there times you keep your blood glucose higher for this reason?’

Ask about how their family, friends and colleagues react to hypoglycaemia

It may be impacting on their significant others too (perhaps even more so). For example:

- ‘Do other people around you worry about you having hypos? How do you respond to their concerns?’

- ‘Does your [significant other] wake up during the night when you are low?’

- ‘Do you think your [significant other] worries about you going low when you are out?’

- ‘If your [significant other] asks you to check your blood glucose or drink juice because s/he suspects you are going low, how do you feel about that?’

- ‘Does having a hypo – or being at risk of hypo – cause any conflicts between you and your partner [family/other]?’

People with diabetes may be reluctant to talk about their experiences of hypoglycaemia because of:

- concerns about losing their driver’s licence or their job

- the associated stigma – losing control as a result of a hypoglycaemic event can be perceived by others as ‘being drunk’ which can cause feelings of embarrassment, shame, and guilt, and can sometimes lead to unnecessary emergency interventions

- concerns that a health professional would expect them to know how to avoid severe hypoglycaemia (particularly if they have lived with diabetes for many years)

- an unrealistic blood glucose target range they may have set for themselves.

If there is an indication that the person experiences fear of hypoglycaemia, you may consider using a validated questionnaire, which will help you both gain a better understanding of what worries them the most.

ASSESS

Validated questionnaire

The Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey-version II Worry scale (HFS-II W) is an 18-item questionnaire for people with type 1 diabetes or those with type 2 diabetes using insulin. A copy is included on page 66. It is the most widely used questionnaire to assess fear of hypoglycaemia. Adapted versions are also available for spouses/partners. Each item is measured on a five-point scale, from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always). The individual item scores can highlight the major concerns related to hypoglycaemia. Based on a study of people with type 2 diabetes, a score of 3 or 4 on any item of the HFS-II W scale indicates fear of hypoglycaemia and needs to be explored further. This is also likely to be the case among people with Type 1 diabetes, although there was no empirical evidence available at the time this guide went to print.

In addition to the HFS-II W, ask about compensatory behaviours the person may use to avoid hypoglycaemia. This provides insights into the person’s acceptance of hyperglycaemia in order to cope with their fear of hypoglycaemia.

You can find the HFS-II W in the full PDF version of this guide (3MB)

Additional considerations

- Is the fear a sign of post-traumatic stress disorder? If a person develops fear of hypoglycaemia after a traumatic hypoglycaemic experience (e.g. causing a car accident, or injuries), it may be a sign of post-traumatic stress disorder. ‘Flashbacks’/memories/dreams of the event, lack of enjoyment, avoidance of activities or situations related to the source of the trauma, and feelings of emotional ‘numbness’ are common reactions in the first days or weeks after a trauma. However, if these symptoms worsen or do not reduce, referral to a mental health professional is recommended for further assessment and treatment.

- Is the fear part of a co-existing anxiety disorder? If this is possible, you may consider using an anxiety questionnaire. Before doing so, check whether the person has been diagnosed with an anxiety disorder now or in the past, and whether they have received treatment.

How can I support a person who experiences fear of hypoglycaemia?

ADVISE

- Now that you have identified that the person has fear of hypoglycaemia, you can advise on the next steps and then, together, decide on an action plan. If the person has completed the HFS-II W, you could use their items scores to guide the conversation. Explain the scores and talk about items with high scores.

- Acknowledge that it is common for people with diabetes to be concerned about hypoglycaemia.

- Explain that ‘fear of hypoglycaemia’ is a normal response to a threat, and a certain amount of fear is okay – because it will help to keep them alert for hypoglycaemic symptoms – but extreme or overwhelming fear is a problem because it can compromise their diabetes management. It can also impair their quality of life, and even the lives of their family members.

- Advise that there are ways to reduce their fears (e.g. strategies that directly focus on the fear, or strategies to prevent or reduce the frequency and severity of hypoglycaemia).

- Explain: that hypoglycaemia is the result of an imbalance between insulin, carbohydrate intake (including alcohol) and physical activity, that not every person with diabetes will experience severe hypoglycaemia (requiring assistance to treat), that most severe episodes are experienced by a minority of people with diabetes, and many of these can be prevented through improving certain self-management techniques and treating mild hypoglycaemia without delay, the mechanisms underlying hypoglycaemic symptoms (e.g. counter-regulation and neuroglycopenia), if it seems helpful for the person.

- Acknowledge that frequent mild (self-treated) hypoglycaemic episodes may be as disruptive as one severe hypoglycaemic episode.

- Indicate that you recognise that the person may choose to keep their blood glucose levels in a higher range to avoid hypoglycaemia in general or in specific situations. However, if this behaviour

- is frequent or persistent, it could have long-term health consequences.

- Offer the person opportunities to ask questions.

- Make a joint plan about the ‘next steps’ (e.g. what needs to be achieved to reduce their fear and the support they may need).

Next steps: ASSIST or ASSIGN?

People with diabetes who experience psychological problems often prefer to talk about this with their diabetes health professionals or their general practitioner (GP) rather than with a mental health specialist. As fear of hypoglycaemia is intertwined with diabetes management, it is best addressed by a diabetes health professional or GP (if they are the main health professional).

If you have the skills and confidence, support the person yourself, as they have confided in you for a reason. A collaborative relationship with a trusted health professional and continuity of care are important in this process; it rarely requires a referral to a mental health specialist.

There will be occasions when it is more appropriate to refer to another health professional. This will depend on:

- the needs and preferences of the person with diabetes

- your qualifications, knowledge, skills and confidence to address fear of hypoglycaemia

- the severity of the fear of hypoglycaemia, and the specific worries identified

- whether other psychological problems are also present (e.g. fear is part of an anxiety disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder triggered by a traumatic hypoglycaemic episode)

- whether other life stressors co-occur

- your scope of practice, and whether you have the time and resources to offer an appropriate level of support.

If you believe referral is needed:

- explain your reasons (e.g. what the other health professional can offer that you cannot)

- ask the person how they feel about your suggestion

- discuss what they want to gain from the referral, as this will influence to whom the referral will be made.

ASSIST

The two main aims when assisting a person with fear of hypoglycaemia are for the person to restore their self-confidence in managing diabetes and to regain a sense of personal control over their glucose levels. For some people, improving their self-management knowledge/skills will reduce their risk of hypoglycaemia and, in so doing, will increase their self-confidence and personal control. For others, fear is more entrenched and unrelated to their knowledge or skills. This will require a focus on fear management. Both approaches are discussed below.

Focusing on enhancing knowledge/skills in hypoglycaemia management

Effective and timely treatment of hypoglycaemia is crucial because of the small window of opportunity to respond before awareness and judgement are compromised.

Review the person’s knowledge about recognising the symptoms of hypoglycaemia and how to treat it. Verify that they understand:

- Not to delay treatment, and to treat with appropriate food/drinks. Explore their barriers to hypoglycaemic treatment (e.g. feeling embarrassed when eating in front of others, dislike of recommended food), and talk about strategies to overcome these barriers.

- The external cues (e.g. the interplay between insulin, food, physical activity, alcohol).

- How to recognise various internal symptoms: physical, cognitive, and emotional. Over the years people with diabetes often rely on one or two hypoglycaemic symptoms, without taking notice of the full range of symptoms (e.g. changes in mood or difficulties in concentrating and performing tasks).

- The symptoms related to the brain not getting enough glucose (e.g. confusion, cognitive impairment). Many people with diabetes and their families are not aware how lack of glucose (e.g. below 3mmol/L) can affect the brain.

- That reduced awareness of hypoglycaemic symptoms can limit their ability to treat hypoglycaemia.

- That hypoglycaemic episodes can be asymptomatic and treatment should therefore be based on a blood glucose reading, not on perceived symptoms.

Provide additional education on hypoglycaemia management to fill identified knowledge gaps, enhance skills and restore confidence:

- Suggest that they keep a record of their hypoglycaemic episodes (e.g. glucose readings below 4mmol/L) for two weeks noting their blood glucose level and experienced symptoms (or lack thereof), identified cues (e.g. delaying or missing a meal, or mismatch between insulin and carbohydrates, after unplanned or more vigorous physical activity, or alcohol consumption) and the actions taken.

Use the recorded information as a learning opportunity, to review their personal reliable hypoglycaemic symptoms and observed causes of it.

- Suggest that they reflect on symptoms that are unusual in the actual situation (e.g. sweating on a cold day, or feeling cold on a hot day) or when their thinking/acting is slower or requires more effort/is more difficult than usual (e.g. difficulty opening a door with a key or tying a shoelace).

- Agree on actions to prevent or reduce their risk of hypoglycaemic episodes.

Support the person to build confidence and assertiveness to respond/act immediately to low blood glucose or hypoglycaemic symptoms. Review their current diabetes management plan:

- Review their diabetes medications (e.g. doses and type of insulin) to exclude the possibility of over-treatment or ‘insulin stacking’.

- Review their self-management knowledge and skills in injection techniques, insulin dose adjustment, carbohydrate counting, blood glucose monitoring, and the impact of alcohol and physical activity on glucose levels (including delayed impact).

- Discuss whether the person will consider using an insulin pump instead of injections and/or using a continuous glucose monitor. Explore the pros and cons for each option.

Encourage the involvement of another person (e.g. a partner, family member, friend, or colleague) to assist in hypoglycaemic management at home/work/school. Identify a person who is well informed and skilled to provide help and administer glucagon (if needed), or is willing to be trained to assist in managing hypoglycaemia.

If the person’s partner/family member worries excessively about hypoglycaemia, suggest that they join the person with diabetes at the next consultation. At the consultation, talk with the partner/family member about the causes of their worry, and how they can support the person with diabetes (and vice versa).

Older people may have cognitive impairment, which makes them more vulnerable to not recognising hypoglycaemic symptoms. In older people, hypoglycaemia symptoms become less specific (e.g. feeling unwell or dizzy) and some are similar to signs of dementia (e.g. agitation, confusion). Furthermore, recurrent hypoglycaemia in older people is associated with decline of physical and cognitive function, which can lead to frailness and disability. For example, older people also are more prone to falls, and if this happens during a hypoglycaemic episode they may be more likely to experience fractures. Guidelines for hypoglycaemia management in older people can be found in ‘The International Diabetes Federation Managing Older People with type 2 Diabetes Global Guideline’

Enhancing self-management knowledge/ skills is likely to be effective if the person’s fear is at a moderate level, and if the person is motivated and skilled to ‘solve the problem’. Explore whether the person fears hyperglycaemia more than hypoglycaemia, as this may be a barrier to making changes to avoid hypoglycaemia.

Focusing on fear management

- Helping the person with diabetes to feel safe needs to be a key priority.

- Before considering any action plan, ask, ‘What do you think is needed to reduce your fear?’ Explore what they could do, or are willing to do and the kind of support they need from you or others.

- If the person lives alone and this is causing fear, talk about prevention of hypoglycaemia (e.g. frequent blood glucose checks, immediate treatment).

- discuss whether the person would find it helpful to have someone check on them (e.g. neighbours or friends) on a regular basis

- inform them about the possibility of a personal medical alarm that may help them to feel safer when alone at home.

- Provide the person with accurate information about their actual risk of hypoglycaemia and challenge their unhelpful ways of thinking about their perceived risk or beliefs of ‘disasters waiting to happen’.

- Develop a stepwise plan. Agree on a blood glucose target range that is both safe and comfortable for the person; this ‘individualised’ target may be higher than the standard targets, when and by how much the target range can be reduced and ‘experiments’ to bring their blood glucose levels back, gradually, to the recommended targets, (e.g. reduce their insulin dose at a time/place that feels safe for them, such as when other people are nearby, or at home).

- It is best to ‘go slow’ and have the person decide when they are ready to take the ‘next step’ to lower their blood glucose levels (i.e. to minimise the risk of increasing their fear or reducing their feelings of safety/personal control).

It is very unlikely that having knowledge about the long-term consequences of hyperglycaemia will motivate a person with fear of hypoglycaemia to reduce their blood glucose levels. Fear of hypoglycaemia is related to the ‘here and now’, not to long-term health risks. For points to consider when supporting someone with fear of hyperglycaemia.

Box 4.3: Fear of hyperglycaemia

Little is known about fear of hyperglycaemia (high blood glucose) and the underlying mechanisms. It may be caused by:

- worrying about the future and the possibility of diabetes complications

- limited knowledge and skills to manage diabetes

- experiencing unpleasant symptoms of high blood glucose levels (e.g. lacking energy or feeling lethargic)

- fearing diabetic ketoacidosis

- perfectionist tendencies.

A person may respond to their fear of hyperglycaemia by keeping their blood glucose levels (too) low, resulting in an increased risk of recurrent mild or severe hypoglycaemia. In turn, this will increase their likelihood of impaired awareness of hypoglycaemic symptoms (due to recurrent hypoglycaemia), and their risk of adverse consequences of undetected hypoglycaemic episodes (e.g. while driving, or at work). Maintaining blood glucose levels within target while avoiding hypoglycaemia and hyperglycaemia is a challenging task and, fear of hypoglycaemia/ hyperglycaemia can co-exist. Micro-managing blood glucose levels (i.e. continually correcting levels with extra insulin or food) may be a sign of high fear of hypoglycaemia/hyperglycaemia.

Understanding the reason(s) for the person’s underlying fear of hyperglycaemia will help you to support them.

If fear is due to limited diabetes self- management knowledge/skills, you may want to offer additional training (e.g. DAFNE).

If fear is due to unpleasant symptoms:

- Advise the person to track their blood glucose levels when they perceive symptoms.

- Problem-solve with the person about how they can manage their perception of the unpleasant symptoms (e.g. have water and sugar-free chewing gum/mints available).

- Assist the person to experiment with increasing their capacity to tolerate and build resilience to the perception of unpleasant symptoms using cognitive coping statements, for example: ‘This feeling may be unpleasant but I can manage it. I’ve survived other unpleasant feelings, such as ... [insert one or more personal examples, e.g. hunger, tiredness, a shaving or paper cut]’.

If the underlying reason is concern about diabetic ketoacidosis:

- Provide education about how diabetic ketoacidosis occurs and how to avoid it.

- Reassure the person that ketoacidosis does not happen by chance.

- Explain that they can manage their risk with regular blood glucose checks and appropriate self-care if ketones are present.

If fear is due to perfectionist tendencies:

- Explain that ‘perfect’ blood glucose levels do not exist, and that minor fluctuations will have little impact – it is the average blood glucose level that is known to be important in preventing long-term complications.

- Talk about ‘coping strategies’ to help them modify their perfectionist beliefs over time. For example, assist them to overcome ‘oversimplification’ (black-and-white thinking), set realistic diabetes goals, and recognise that self-care is a process, not an outcome.

Box 4.4: Worries about long-term complications

Research has shown consistently that people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes are very concerned about developing serious complications. Diabetes does, indeed, increase the risk of long-term complications, when glucose levels have been above target over a long period.

However, people with diabetes often overestimate their risk of complications which can result in unnecessary high levels of fear. People who are very concerned about complications are also more likely to be emotionally distressed, anxious, and depressed.

Diabetes education has a strong focus on the risk of long-term complications. This may trigger (unrealistic) severe concerns, especially in people who do not feel equipped to maintain their blood glucose levels within recommended targets. Compared to providing general risk information, discussing individualised risk is more effective in adjusting the person’s risk perceptions and enhancing engagement in healthy self-care behaviours. Also, shifting the focus from ‘scary’ messages about complications to strategies to maintain blood glucose in optimal ranges is more encouraging and more likely to be successful.

To address the person’s worries about complications:

- Ask the person about the diabetes complication(s) they are most worried about.

- Gain a better understanding of their knowledge, beliefs about the seriousness of complications, their perceived risk of developing complications and related feelings. For example, if they have family members with diabetes who have (had) diabetes complications this can exaggerate the individual’s perception of their own risk. This insight will enable you to provide individualised, relevant information about the person’s actual risk.

- Advise them that diabetes complications are avoidable and that not every person with diabetes develops complications and do not develop ‘overnight’ and that minor lapses/blood glucose levels occasionally ‘out of target’ are not cause for concern; it is persistently elevated glucose levels (over long periods of time) that place a person at higher risk of developing complications.

- Explain that keeping blood glucose levels within target will prevent ‘rebound’ high blood glucose levels after hypoglycaemia and living with hypoglycaemia does not guarantee that they will avoid long-term complications.

- Reassure them that rates of complications have reduced considerably in recent years due to more effective, modern diabetes treatments and technologies.

- Use the conversation to inform an action plan. For example, together, develop strategies for preventing complications/maintaining blood glucose levels within target.

ASSIGN

If a decision is made to refer, consider:

- a diabetes specialist nurse, for hypoglycaemia management, general diabetes education (e.g. to review blood glucose monitoring and injection techniques/ skills), and support

- an diabetologist for a review of the current diabetes regimen

- a structured type 1 diabetes education program, for example, DAFNE; this group education has been shown to halve the rate of severe hypoglycaemia and improve awareness of hypoglycaemic symptoms

- a mental health professional (e.g. a psychologist or psychiatrist, preferably with an understanding of diabetes) if the strategies in ASSIST do not reduce the person’s fear of hypoglycaemia or for post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of an unprocessed’ traumatic hypoglycaemic experience in the past.

If you refer the person to another health professional, it is important:

- that you continue to see them after they have been referred so they are assured that you remain interested in their ongoing care

- to maintain ongoing communication with the health professional to ensure a coordinated approach.

ARRANGE

Depending on the action plan and the need for additional support, it may be that extended consultations or more frequent follow-up visits (e.g. once a month) are required until the person feels less fearful about hypoglycaemia and is confident in sustaining the behavioural changes. Encourage them to book a follow-up appointment with you within an agreed timeframe. Telephone/ video conferencing may be a practical and useful way to provide support in addition to face-to-face appointments.

Special attention needs to be given to those who have recently experienced a traumatic hypoglycaemic episode, to assess both their behavioural and emotional responses in the weeks following the episode.

At the follow-up appointment, use open-ended questions to enquire about the person’s progress, for example:

- ‘Last time we talked about your concerns about having hypos. How do you feel about it now?’

- Explore their concerns, and whether they experienced any hypoglycaemic episodes since you last saw them, and if so, explore the circumstances, perceived symptoms, causes, and their actions and feelings. Continue: ‘We talked about making some changes to your diabetes management to reduce your hypos. How has this worked out for you?’ Explore what has/has not worked, for example, obstacles or concerns.

- ‘Last time we talked about you seeing a psychologist to help you with your fear of hypos. How has this worked out for you?’ If not, enquire what else is needed.

- If you previously used a questionnaire (e.g. HFS-II W), you could consider using it again to reassess their level of fear of hypoglycaemia.

Case study

- Irena

- 31-year-old woman, moved from Greece to the UK with her husband several years ago

- Type 1 diabetes (diagnosed 16 years ago), managed with four daily injections

- Health professional: Dr Anna Garvin (endocrinologist)

Be AWARE

Irena has been seeing Anna on a quarterly basis. They have established a collaborative, trusting relationship. They have focused on optimising Irena’s diabetes management plan, as her daily blood glucose and HbA1c levels are above target. Irena is very motivated and open to Anna’s advice to improve her diabetes outcomes. Irena has participated in an DAFNE course, which she found useful. She and Anna have discussed the pros and cons of insulin pumps, but Irena does not want to be attached to a device ‘24/7’. Irena thinks she is ‘doing well’ with her diabetes management since DAFNE, so she is not concerned about long-term diabetes complications. Anna wonders whether the lack of improvement in Irena’s blood glucose levels could be due to how Irena feels about her diabetes management.

ASK

At the next visit, while Irena is waiting for her appointment, Anna invites her to complete the Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire. She explains to Irena, ‘Over the last few months we have been focusing on your diabetes treatment, and you have put a lot of effort into improving your management. I thought it might be good to talk about how you are feeling about your diabetes. This questionnaire lists common problems that people with diabetes experience on a daily basis. Would it be OK for you to answer these questions while you wait? Then, we can talk about it when you come in to see me.’ Irena is happy to complete the questionnaire.

ASSESS

Most of Irena’s scores on the PAID are in the lower range (scores 1 or 2). She scores 3 (moderate problem) on three items:

- ‘worrying about low blood glucose reactions’

- ‘feelings of guilt and anxiety when off track with diabetes management’

- ‘feeling burned out’.

Anna enquires about Irena’s experience filling in the form. Irena says, ‘It was OK’, but she notices that Irena avoids eye contact and becomes restless. Anna says, ‘I may be wrong, but I get the feeling that these questions have upset you’, Irena starts crying. Anna gives her some time to express her emotions, then continues: ‘It’s been tough. Would you like to talk about it?’ She pauses to give Irena time to consider and respond to the question.

Irena tells Anna about a severe hypo – and resulting accident – she had a few years ago when she was driving home from work. Irena was taken to the hospital. Her recovery went well and she was back at work after three months, but the accident has had ongoing effects. Irena:

- regularly has bad dreams about causing an accident and hurting other people

- continues to blame herself for not treating the impending hypo in time

- no longer drives a car, which affects her social life and independence

- avoids going out alone

- is having marital problems as a result of her concerns.

At first, her husband was very supportive, but now he does not understand why Irena does not get on with her life. He is also unhappy that he has to drive her around.

Anna acknowledges the impact this severe hypo has had on Irena’s life for so many years. She further explores whether Irena has reduced her insulin, which could explain her high blood glucose levels. ‘Some people may take less insulin after they have been involved in such an accident. Have you reduced the amount of insulin to avoid another severe hypo?’ Irena replies that she has, indeed, been taking less insulin than required over a long period of time.

ADVISE

Anna thanks Irena for opening up about this experience and asks how she is feeling now. ‘Every time I came to see you, I wanted to tell you about this accident. But I couldn’t do it. I am really scared when I see these high numbers on my meter but I’m also scared of having another accident.’ Anna asks Irena if the timing is right to talk about the kind of support that is available to work through her traumatic experience.

ASSIST

Anna asks whether Irena has considered consulting a psychologist for help with processing the trauma and overcoming her fear of hypoglycaemia. Irena has thought about it, but doesn’t know where to start. Anna suggests that she contact her GP for advice and possible referral to a psychologist.

ARRANGE

They agree on a time for the next visit. Anna explains that while Irena is consulting the psychologist, they will together work out a diabetes management plan that is both ‘safe’ and achievable for Irena. In time to come, they will talk about how best to reduce these high readings without increasing Irena’s risk of hypos. But overcoming the fear is the first priority because, if this remains unresolved, it will be a major barrier to making any changes to her diabetes care plan.

Case study

- Aaron

- 25-year-old man, living with his wife, Hannah, and one-year-old daughter, Leila

- Type 1 diabetes (diagnosed 20 years ago). Typically injects insulin four times per day and checks his blood glucose at least 10 times a day. His HbA1c ranges between 41 and 46 mmol/mol (5.9 and 6.4%)

- Health professionals: Dr Paul Asher (endocrinologist) and Steven Mazumdar (diabetes specialist nurse)

Be AWARE

Aaron is highly motivated and well-informed about diabetes. But Dr Asher has concerns about Aaron’s frequent hypoglycaemic episodes (on average 10 episodes per week that he can self-treat). He is aware that Aaron does a lot of finger pricks per day and that he often injects extra insulin to bring his blood glucose level down. Last month, Aaron had a severe hypo while surfing with friends, and he had to be rescued by a lifesaver. Dr Asher has referred Aaron to Steven, one of the diabetes specialist nurses in the team, to review his diabetes management plan with the aim to reduce the frequency of hypoglycaemia.

ASK

Steven welcomes Aaron and his wife Hannah to the appointment. He asks Aaron the purpose of his visit. Aaron replies ‘I don’t know. Dr Asher asked me to come and see you. But all is going well, my last HbA1c was 6.1%, and my tests were all fine’. Hannah, clearly unhappy with Aaron’s reaction, tells Steven about Aaron’s severe hypo whilst surfing and that he has at least one hypo every day. Aaron responds that ‘it’s not a big deal, it’s to be expected… don’t worry, I know what I'm doing’.

Steven asks Aaron about his history of hypoglycaemia and his recent severe episode. He learns that:

- The surfing incident was not Aaron’s first severe hypo this year. Hannah treated his last severe hypo at home with glucagon.

- Aaron checked his blood glucose before leaving home; it was 3.7 mmol/L. He knows most people would consider this to be ‘too low’.

- Aaron often surfs with low blood glucose, ‘Usually it is okay. I have carbs with me and as soon as I feel my sugar dropping I eat some’.

- This time, Aaron did not respond when he felt his glucose levels dropping: ‘I knew my blood sugar was getting low but I couldn't be bothered getting out of the water for food… It was stupid of me’.

- Aaron feels ‘best when my sugar sits between 3.5 and 7.5’. He gets annoyed if his blood glucose gets higher than 8.0mmol/L and will give himself ‘a few units [of insulin] to bring it down’.

Steven also asks Hannah about her feelings. Hannah tells him that she:

- is very worried because Aaron has many ‘lows’

- is concerned that Aaron will have a hypo when he is alone with Leila and will be unable to take care of her or might even drop her

- knows that Aaron drives with low blood glucose levels (below 4 mmol/L) and is afraid that he will have an accident while Leila is in the car

- is frustrated that Aaron does not appreciate how worried she feels.

Steven considers whether Aaron may be more anxious about hyperglycaemia than about hypoglycaemia and that maybe he is avoiding blood glucose levels above 8 mmol/L by taking more insulin than required.

Steven further explores Aaron’s motivations for keeping his blood glucose levels within such narrow targets: ‘Aaron, it sounds like keeping your blood glucose level below 8 is very important to you. Could you tell me a bit more about it?’

Aaron says that he:

- does not want his diabetes to stop him from surfing and building a successful career

- will do anything to prevent long-term complications, as they will get in the way of his plans

- is happy with how he is managing his diabetes right now and feels ‘in control’

- has heard Hannah’s concerns today, but acknowledges that in the past he has avoided having that conversation with her

- wants Hannah to trust him to be able to look after their baby.

ADVISE

Steven acknowledges the effort that Aaron puts into his diabetes management and Hannah’s concerns about the well-being of her family. Although he understands that Aaron is well-informed about his diabetes, Steven reiterates to Aaron and Hannah:

- how hypoglycaemia could impair his brain and that it makes it hard to treat a low blood glucose level in a timely way

- that Aaron's actual risk of complications, based on his past HbA1c results and annual screenings, is relatively low

- the consequences of living ‘on the edge’ of hypoglycaemia.

ASSIST

Steven acknowledges that it has not been easy for them to have this conversation. But Aaron and Hannah are both glad that Steven took the time to ask these questions – they could not have had this conversation at home. Steven notices that Hannah’s words have had a big impact on Aaron.

Steven provides them with some strategies about how the couple could ‘meet in the middle’ to reduce Aaron’s fear of hyperglycaemia and Hannah’s fear of hypoglycaemia. He also suggests that they individually write down the kind of support that would be helpful to them. Then, together, talk about and agree on a realistic plan for mutual support.

ARRANGE

Steven suggests that Aaron and Hannah take some time to think about what has been said today and that the three of them meet again in two weeks to see how things have been going. Aaron and Hannah agree.

Questionnaire: The Hypoglycaemia Fear Survey-II Worry (HFS-II W) scale

Find the HFS-II W scale, and information on how to use it on the full Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB)

Resources

For health professionals

Peer-reviewed literature

- A critical review of the literature on fear of hypoglycaemia in diabetes: implications for diabetes management and patient education. Description: Based on a review of 34 papers, the authors have integrated the findings about fear of hypoglycaemia, predictors and correlates, its impact on behaviour and potential benefits of intervention to reduce fear. Source: Wild D, von Maltzahn R, et al. Patient Education & Counselling. 2007;68:10-15.

- The impact of hypoglycaemia on quality of life and related patient-reported outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a narrative review. Description: This review provides a synthesis of research findings, showing that hypoglycaemia is associated with depressive symptoms and higher anxiety, impaired ability to drive, work and function in people living with type 2 diabetes. Source: Barendse S, Singh H, et al. Diabetic Medicine. 2012;29:293-302.

- Managing hypoglycaemia in diabetes may be more fear management than glucose management: a practical guide for diabetes care providers. Description: This paper describes strategies that can be integrated into routine diabetes care to support people with diabetes and fear of hypoglycaemia. Source: Vallis M, Jones A, et al. Current Diabetes Reviews. 2014;10:364-370.

- Evidence-informed clinical practice recommendations for treatment of type 1 diabetes complicated by problematic hypoglycaemia Description: This review paper summarises the current evidence and recommends strategies for problematic hypoglycaemia in people with type 1 diabetes. Source: Choudhary P, Rickels MR, et al. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1016-1029.

- Impact of fear of insulin or fear of injection on treatment outcomes of patients with diabetes Description: This systematic review summarises the findings of six research papers focusing on fear of insulin and fear of injections. Source: Fu AZ, Qiu Y, et al. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2009;25:1413-1420.

For people with diabetes

Select one or two resources that are most relevant and appropriate for the person.

Providing the full list is more likely to overwhelm than to help.

Support

- Diabetes UK Diabetes UK is the major organisation for support, information and research relating to all types of diabetes mellitus. Phone: 0345 123 2399 Email: helpline@diabetes.org.uk URL: www.diabetes.org.uk

- Peer support for diabetes. There are various ways of accessing peer support in the UK to share experiences and information with others living with diabetes. See Appendix B for full listing

Information

- Fear of hypoglycaemia. Information leaflet for people with diabetes about fear of hypoglycaemia. The leaflet includes suggestions that the person may try in order to reduce their fear, and offers suggestions for support and additional information. This leaflet can be downloaded here (PDF, 44KB)

- Diabetes UK website pages about hypo anxiety. A webpage explaining some of the causes of hypo related anxiety and practical strategies and techniques to manage this. Source: Diabetes UK, 2018. URL: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/life-with-diabetes/hypo-anxiety

- Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE). DAFNE is a five-day structured type 1 diabetes training programme. People attend in small groups, with others who have type 1 diabetes, to learn more about self-managing the condition. Studies have shown that DAFNE can help people with problematic hypos. On average, rates of severe hypo are halved following DAFNE training. Courses are available in many areas of the UK and you can be referred by your diabetes health professional. URL: www.dafne.uk.com

- Managing Fear, Anxiety and Worry. A chapter in the book ‘Diabetes and Wellbeing’ by Dr Jen Nash, explaining fear of hypoglycaemia (and other fears) and giving strategies to cope. Book Reference: Diabetes and Wellbeing: Managing the Psychological and Emotional Challenges of Diabetes Types 1 and 2. 2013. John Wiley and Sons Ltd Chapter 5, pages 80-108. URL: https://www.wiley.com/en-gb/Diabetes+and+Wellbeing:+Managing+the+Psychological+and+Emotional+Challenges+of+Diabetes+Types+1+and+2-p-9781119967187

- Diabetes burnout: what to do when you can’t take it anymore. Chapter 17 of this book focuses on ‘Worrying about hypoglycaemia’ (page 286) and Chapter 10 on ‘Worrying about long-term complications’ (page 159). The book provides easy-to-use strategies to overcome these concerns. It is available for purchase from the Behavioral Diabetes Institute website. Source: Polonsky W (1999), American Diabetes Association, ISBN: 1-58040-003-7. URL: www.behavioraldiabetesinstitute.org

See Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB) for our full list of references