Key messages

- Diabetes distress is the emotional distress resulting from living with diabetes and the burden of relentless daily self-management.

- Severe diabetes distress affects one in four people with type 1 diabetes, one in five people with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes, and one in six people with non-insulin treated type 2 diabetes.

- Greater diabetes distress is associated with sub-optimal diabetes self-management, HbA1c, and impaired general emotional well-being.

- Diabetes distress is sometimes mistaken for, and is more common than, depression.

- The Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) scale is used to identify diabetes distress and to guide conversations about diabetes distress.

- Diabetes distress is best managed within the context of diabetes care.

- Although greater diabetes distress tends to be associated with higher HbA1c, optimal HbA1c is not necessarily an indicator of low diabetes distress.

Practice points

- As diabetes distress is relatively common, and also impacts upon self-care, it is important that every consultation includes opportunity for the person to express how they are feeling about life with diabetes.

- Remain mindful that certain treatment options may increase the burden of diabetes self-management and increase the likelihood of diabetes distress.

- Collaboratively set an agenda for the consultation – talk about what each of your priorities are for today and agree about how much time to dedicate to each topic.

How common is diabetes distress?

Evidence from 50 studies undertaken across the world tells us that one in four people with type 1 and one in five people with type 2 diabetes have high levels of diabetes distress that is likely to be negatively effecting how they manage their diabetes.

|

|

What is diabetes distress?

Diabetes distress (also known as diabetes-specific distress or diabetes-related distress) is the emotional response to living with diabetes, the burden of relentless daily self-management and (the prospect of) its long-term complications. It can also arise from the social impact of diabetes (e.g. stigma, discrimination, or dealing with other people’s unhelpful reactions or their lack of understanding) and the financial implications (e.g. insurance and treatment costs) of the condition.

Diabetes distress occurs on a continuum defined by its content and severity. This emotional distress, to a greater or lesser degree, is part of having to live with and manage diabetes. It can fluctuate over time and may peak during challenging periods, for example, soon after diagnosis, during major changes in treatment regimen, or at diagnosis/ worsening of long-term complications. It can also peak at times of heightened general stress, when the added burden of diabetes self-care becomes too much. If left untreated, mild diabetes distress may develop into severe diabetes distress and/or depression.

Living with diabetes is challenging. The most frequently reported problem areas among people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes are ‘worrying about the future and the possibility of serious complications’ and ‘experiencing feelings of guilt and anxiety when diabetes management goes off track’. Although there are common stressors irrespective of the type of diabetes, distress can differ by diabetes type (e.g. for type 1 diabetes more often related to the insulin treatment and hyper/hypoglycaemia, for type 2 diabetes more often related to social consequences, food restriction, and obesity).

The impact of these diabetes-related feelings should not be underestimated. Managing diabetes is a ‘24/7’ activity, involving the continual need to make decisions, and take actions, with often unexpected and unsatisfactory outcomes. Doing everything ‘as recommended’ is no guarantee of stable blood glucose levels – doing exactly the same things today as the day before can result in very different outcomes. The accumulation of these problems and frustrations may lead to ‘diabetes burnout’ (see Box 3.1) and disengagement from diabetes care.

Diabetes distress involves emotional symptoms that overlap with several recognised mental health conditions, such as depression. Despite their similarities, depression and diabetes distress are different constructs and require different assessment and management strategies. Unlike major depression, diabetes distress does not assume psychopathology – it is an expected reaction to diabetes whereas depression refers to how people feel about their life in general.

Greater diabetes distress is associated with adverse medical and psychological outcomes, including:

- sub-optimal self-management (e.g. reduced physical activity, less healthy eating, not taking medication as recommended, and less frequent self-monitoring of blood glucose)

- elevated HbA1c

- more frequent severe hypoglycaemia

- impaired quality of life.

Box 3.1: Diabetes burnout

Diabetes burnout is a state of physical or emotional exhaustion caused by the continuous distress of diabetes (and efforts to self manage it).Typically, the individual feels that despite their best efforts, their blood glucose levels are unpredictable and disappointing.

This often leads to feeling helpless and disengaged from diabetes management. People with diabetes burnout ‘can’t be bothered’ with the continual effort required to manage diabetes. This state of mind can be temporary or it may be ongoing. These individuals are sometimes described by health professionals as being ‘difficult’, ‘non-compliant’, or ‘unmotivated’, while they are actually struggling with the relentlessness of managing a life-long condition.

Signs of diabetes burnout include:

- disengagement from self-care tasks (e.g. skipping insulin doses/tablets, or not monitoring blood glucose)

- unhealthy or uncontrolled eating

- risk-taking behaviours

- non-attendance at clinic consultations.

People with diabetes burnout understand the importance of diabetes self-management for their future health, but feel unable to take control of their diabetes. If and when someone with diabetes burnout attends their consultation, they are rarely open to any advice for change that you may offer: ‘I’ve tried that before but it didn’t work’; ‘I stopped doing finger-pricks because I know my blood sugar will be too high anyway’. This disengagement from self-care can increase their fears of developing long-term complications and sense of powerlessness to take control. As clinical psychologist, Dr William Polonsky, describes, ‘they are at war with their diabetes – and they are losing it’.

Diabetes burnout can co-occur with depression, anxiety, and negative mood. In contrast to diabetes distress, very little research has been conducted specifically about diabetes burnout. The best way to prevent diabetes burnout is to regularly monitor for diabetes distress so that you can offer timely assistance to address concerns as they arise.

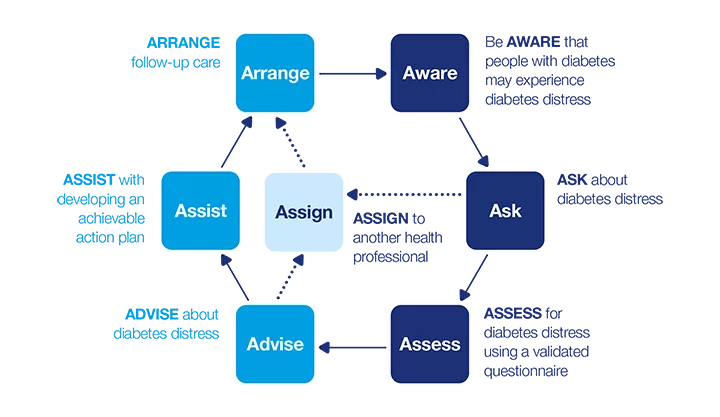

7 As model: Diabetes distress

This dynamic model describes a seven-step process that can be applied in clinical practice. The model consists of two phases:

- How can I identify diabetes distress?

- How can I support a person who experiences diabetes distress?

Apply the model flexibly as part of a person-centred approach to care.

How can I identify diabetes distress?

Be AWARE

Diabetes distress can present itself in many ways. Some common signs to look for include:

- sub-optimal HbA1c or unstable blood glucose levels

- not attending clinic appointments

- reduced engagement with diabetes self-care tasks (e.g. less frequent monitoring of blood glucose or skipping medication doses)

- ineffective coping strategies for dealing with stress (e.g. emotional eating)

- multiple negative life stressors or chronic stress distinct from diabetes (e.g. financial problems, unemployment, homelessness)

- impaired relationships with health professionals, partners, family or friends

- appearing passive or aggressive during consultations.

Even if HbA1c or blood glucose levels are within target, this does not mean that the person is free of diabetes distress. Achieving these targets may require intensive efforts that are potentially impacting on other areas of their life (e.g. social activities, quality of life) and are unsustainable. Remain mindful that recommending changes to diabetes self-management (e.g. recommending more frequent blood glucose monitoring) may increase the burden of diabetes and, thereby, has the potential to increase diabetes distress.

ASK

It is advisable that you ask about diabetes distress on a routine basis, as part of your person-centred consultation, to explore the impact of diabetes on the person’s daily life and well-being.

Ask open-ended questions. You can preface these by acknowledging the expected daily challenges of living with diabetes, for example, ‘Many people that I see find living with diabetes quite challenging’. This ‘normalises’ diabetes distress.

There are many ways you can ask about diabetes distress; choose an approach that you find most comfortable and one that best suits the person with diabetes. Here are some examples of open-ended questions you could use:

- 'What is the most difficult part of living with diabetes for you?’

- ‘What are your greatest concerns about your diabetes?’

- ‘How is your diabetes getting in the way of other things in your life right now?’

These questions offer the person an opportunity to:

- raise any difficulties (emotional, behavioural or social) that they are facing

- express how particular diabetes-related issues are causing them distress and interfering with their self-care and/or their life in general.

One example of how to follow up the conversation could be: ‘It sounds like you're having a difficult time with your diabetes. The problems you describe are quite common. And, as you also said, they often have a big impact on how you feel and how you take care of your diabetes. If you like, we could take some time to talk about what you and I can do to reduce your distress. What do you think?’

Additional considerations

- People may not expect to be asked about their emotions during a diabetes consultation. A distinct disconnect between you and the person with diabetes may be an indication of diabetes distress. For example, the person may not be listening to what you say, or may reject your suggestions for changes to their diabetes management plan or lifestyle. Also, look out for people who regularly skip or do not attend their appointments.

- People with diabetes may not be aware of diabetes distress and may interpret their experiences as depression.

- Diabetes distress fluctuates over time. A person may not be experiencing diabetes distress today but they may be the next time you see them. Life circumstances can change quickly, and stressors (diabetes-related or not) may disrupt blood glucose levels or self-care behaviours and worsen diabetes distress. Therefore, at every consultation, it is always a good idea to ask the person how they are going with their diabetes.

If the person indicates that they are experiencing concerns or distress about diabetes, you may want to explore this further. Using a validated questionnaire will help you both to get a better understanding of the specific problems the person is facing. Importantly, it will also give you a benchmark for tracking the person’s distress over time.

However, only use a questionnaire if there is time during the consultation to talk about the scores and discuss with the person what needs to happen in order to address the identified ‘problems’. You can find more information about using a questionnaire on the full Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB)

ASSESS

Validated questionnaire

The Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) is a 20-item questionnaire, widely used to assess diabetes distress. Each item is measured on a five-point scale, from 0 (not a problem) to 4 (a serious problem). The scores for each item are summed, then multiplied by 1.25 to generate a total score out of 100; with total scores of 40 or more indicating severe diabetes distress. Apart from the total score, an individual item score of 3 or more indicates a ‘problem area’ or concern, and should be further explored in the conversation.

To follow up on the completion of the PAID you may want to ask:

- ‘How did you feel about answering these questions?’

- ‘When looking at your scores, does anything stand out for you?’

Another widely used questionnaire for diabetes distress is the Diabetes Distress Scale (DSS), which has 17 items. A new version of the DDS specifically designed for people with type 1 diabetes (T1-DDS) has been validated recently in the USA and Canada.

Not all stressors that can lead to diabetes distress are addressed in the existing validated questionnaires, and therefore exploration through open-ended question is recommended to identify other causes of diabetes distress.

Additional considerations

No diabetes distress – what else might be going on?

- If the person’s responses to the questionnaire do not indicate the presence of diabetes distress, this may be because they are reluctant to open up about their distress or may feel uncomfortable disclosing to you that they are not ‘on top’ of their diabetes. Therefore, a very low score does not necessarily mean that the person is not experiencing diabetes distress. It may be that they are not yet ready to share that experience with you. It may take time for them to express their diabetes-related concerns and problems – or they may feel more comfortable talking about it with someone else. Acknowledging that many people experience difficulties and distress in managing their condition on a daily basis can be one way to show your support and openness to talk about their concerns; they may be ready to talk at future consultations.

- If not diabetes distress, consider other psychological problems, for example, depression, anxiety or general psychological distress. Using a general psychological distress questionnaire (such as the Kessler-10) could be informative in this instance, as the person may be experiencing other life stressors that are causing general distress and impacting on their diabetes self-management and outcomes. Explaining and normalising diabetes distress is the first step to addressing it.

How can I support a person who experiences diabetes distress?

ADVISE

Now that you have identified what is causing the person’s diabetes distress, you can advise them on the options for the next steps and then, together, decide on an action plan.

When using the PAID, the scores on the individual items are a useful first indication of the major problem(s) or concerns for the person and will guide the conversation.

- Explain what diabetes distress is and that many people with diabetes experience it:

- Explain the signs and consequences of diabetes distress (e.g. the impact on their daily self-management and well-being).

- Acknowledge the significant daily efforts required to manage diabetes – this by itself may reduce the distress.

- ‘Normalise’ negative emotions about diabetes.

- If a person is self-blaming (e.g. ‘I am useless’ or ‘I can never get it right’), explain that diabetes outcomes are not a reflection of who they are as a person; diabetes is not about being ‘good’ or ‘bad’, or about being ‘a failure’ (see Appendix A). Instead remind them that diabetes can be difficult to manage, so focusing on what they are doing well, despite less than ideal outcomes, is sometimes ‘good enough’.

- Offer the person opportunities to ask questions about what you just discussed.

- Make a joint plan about the ‘next steps’ (e.g. what needs to be achieved to reduce diabetes distress and the support they may need).

Next steps: ASSIST or ASSIGN?

People with diabetes who experience psychological problems often prefer to talk about this with their diabetes health professionals or their general practitioner (GP) rather than with a mental health specialist.

As diabetes distress is so common and intertwined with diabetes management, it is best addressed by a diabetes health professional (or the GP if they are the main health professional). If you have the skills and confidence, support the person yourself, as they have confided in you for a reason. A collaborative relationship with a trusted health professional and continuity of care are important in this process.

There will be occasions when you will need to refer the person to another health professional. This will depend on:

- the needs and preferences of the person with diabetes

- your knowledge, skills and confidence to address the problem area(s)

- the severity of the diabetes distress, and the specific problem(s) identified

- whether it is combined with other significant life stressors

- whether other psychological problems are also present, such as depression or anxiety

- your scope of practice, and whether you have the time and resources to offer an appropriate level of support

If you believe referral to another health professional is needed:

- explain your reasons (e.g. what the other health professional can offer that you cannot)

- ask the person how they feel about your suggestion

- discuss what they want to gain from the referral, as this will influence to whom the referral will be made.

ASSIST

Explore the most appropriate support for the individual, for example, diabetes education or revising their management plan, advice on lifestyle changes, emotional or social support, or a combination of these.

You might ask questions to inform the action plan, such as:

- ‘It sounds like you are struggling with several aspects of your diabetes care. Which of these would you most like to talk about today?’

- ‘You said you feel angry and guilty when you think about your diabetes. Could you tell me what exactly makes you feel this way?’ Explore whether it is the self-management tasks, the diabetes outcomes (e.g. high blood glucose levels) leading to these feelings, or whether it is related to how diabetes impacts on other aspects of their life (e.g. feelings of not being a ‘good’ parent because of diabetes, or diabetes interfering with their work or social life).

- ‘You have indicated that you are concerned about developing complications. Could you tell me a bit more about your concerns?’ The person’s response will help you to identify unrealistic concerns so you can provide personalised information about their actual risk and preventative actions. It will give you a better understanding of the person’s specific concerns, for example, whether their concerns relate to the risk of vision impairment, problems with their feet, or other complications. Many people with diabetes overestimate their risk of complications and feel helpless to prevent them. This causes significant distress and can lead to disengagement with their self-care.

- ‘According to your answers on the PAID, you feel supported in some aspects of your diabetes management but not in others, is that correct? Can you give me an example of this?’

- ‘You feel that you are not getting support from your partner or family/friends. Is this your overall feeling?’

Additional considerations

- Reflect on aspects that are going well, to counterbalance ‘problems’. Many of our conversations focus on problems and problem solving. However, it is just as crucial to explore what is going well; that is, in what aspect(s) of diabetes management does the person feel confident? This will highlight their strengths and skills, which could be applied to address their current problems.

- Agree on an agenda for the consultation. Agree with the person about the time dedicated to talk about their concerns and the issues you both would like to address today. In practice, there is usually a big overlap between both agendas but it is important not to assume this is the case. If there is insufficient time to cover everything, suggest a follow-up consultation with you or someone else in your team who could provide the additional support.

- Stay open to the idea that people with diabetes can have safe, planned breaks from their usual diabetes management (see Box 3.2)

- If the diabetes distress persists, a more intensive approach may be needed. Although diabetes distress is best addressed during the routine consultation, if the person shows no improvement it may be necessary to reconsider referring the person to a mental health professional or assess whether there are additional or other underlying psychological problems, for example, depression or anxiety.

Box 3.2: Taking a safe break from diabetes

It is unrealistic to expect people with diabetes to monitor their health vigilantly 24 hours-a-day, seven days-a-week. As this guide outlines, lack of motivation due to diabetes distress and/ or depression can have serious negative consequences for a person’s health. People so-inclined will take breaks from actively managing their diabetes with or without your support. Enabling them the freedom to take short breaks every now and then will increase their chances of maintaining motivation to take good care of their health in the long-term.

Where do I start?

Work with the person to meet their needs. Remember to put yourself in their shoes and think what it would be like for you to manage diabetes 24/7. For example, if they are struggling to check their blood glucose several times a day, consider reducing the number of checks required for a period of time. In the meantime, work with them on their concerns regarding this issue (e.g. through supportive counselling or goal-setting). Regardless of the issue they are facing, it is important to remain supportive and encouraging. This will eliminate any feelings of guilt that the person may be experiencing for not managing their diabetes ‘perfectly’. Remind the person that you understand managing diabetes is a full-time job and appreciate that everyone needs a break now and then.

ASSIGN

If a decision is made to refer, consider:

- a diabetes specialist health professional for difficulties with diabetes management and support

- a mental health professional such as IAPT, a psychologist or psychiatrist (preferably with an understanding of diabetes) for stress management or if other emotional problems such as depression or anxiety or more complex psychopathology are underlying the diabetes distress.

For some people an intensive psychological intervention may be the best option to reduce severe diabetes distress. Cognitive behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing and brief solution-focused therapy have been successfully applied in diabetes.

These health professionals can be accessed via your local Improving Access to Psychological Therapies service (IAPT) by you, by the person self-referring or by a GP referral

If you refer the person to another health professional, it is important:

- that you continue to see them after they have been referred so they are assured that you remain involved in their ongoing care

- to maintain ongoing communication with the health professional to ensure a coordinated approach.

ARRANGE

Depending on the action plan and the need for additional support, it may be that extended consultations or more frequent follow-up visits (e.g. once a month) are required until the person feels better skilled or stronger emotionally. Encourage them to book a follow-up appointment with you within an agreed timeframe. Telephone/ video conferencing, text or email support may be a practical and useful way to provide support in addition to face-to-face appointments or text or email support is valued.

Monitor people with identified diabetes distress closely, so that you can assess their level of distress and how it may change over time. The advantage of using the PAID scale routinely is that this systematic monitoring allows you to compare scores over time. Then you can be proactive in picking up early signs or a relapse.

At follow-up contacts, use open-ended questions to enquire about the person's progress. For example:

- ‘Last time we talked about you feeling overwhelmed with all the tasks you have to do in managing your diabetes. We agreed on making a couple of changes to your management and lifestyle. How has this worked out for you?’ For example, explore what has worked, obstacles, concerns, and whether any changes to the action plan are needed.

- ‘Last time we talked about you seeing a diabetes specialist nurse to help you [get your blood glucose levels back on track]. You felt frustrated about [these high numbers].’

You could then ask the following questions:

- ‘Has this been helpful?’ If yes ‘How is this helpful for you?’ If no, ‘What do you think needs to happen so that it will help?’

- ‘What changes have you made?’

- ‘Which changes were helpful/not helpful?’

- ‘How do you feel now about [your blood glucose levels]?’

- ‘Are you happy to continue with [these changes]?’ Explore response.

- ‘How do you feel about [these changes]?’

Case study

- Elizabeth

- 62-year-old woman, living with her husband

- Type 2 diabetes for 10 years; overweight. Oral medications for diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol

- Health professional: Dr Andrew Brown GP

Be AWARE

Andrew is aware that UK and international guidelines recommend assessment for diabetes distress in people with type 2 diabetes. He invites Elizabeth to complete the PAID while she is waiting for her consultation.

ASK and ASSESS

When Elizabeth hands over the completed questionnaire, Andrew notices immediately that 12 of 20 items have scores of three and four. It is clear that Elizabeth is feeling highly distressed about her diabetes. Andrew has known her for a long time and is aware that she has been having some difficulties managing her diabetes, but he did not realise she was struggling so much. Her medical results had been improving.

He thanks Elizabeth for completing the questionnaire and asks ‘How was it for you to answer all these questions?’ Elizabeth responds, ‘Well, it does not look good, does it? I am really angry! But, it feels good that I could say how I really feel about diabetes’. Andrew suggests that they first look at her questionnaire responses, before checking her blood pressure and looking over recent blood test results; and Elizabeth agrees.

The high PAID scores are mostly related to the emotional impact of living with diabetes and difficulties with diabetes management. Elizabeth confirms that, indeed, these are the most important problems she is experiencing at the moment. Andrew asks Elizabeth to tell him a bit more about these difficulties. Elizabeth responds, ‘It is so hard for me to control what I eat, to take all these tablets every day and to walk my dog in the morning. Most of the time I do all these things, but it is a big effort! I am not sure how long I can keep doing this. Sometimes I wonder how I manage to get out of bed, eat, let the dog out, and go to work. At night I say to myself “I made it through another day”. I can’t keep my house clean. And that is really bad! I feel guilty when my house is a mess but I am really too tired’.

ADVISE

Andrew reflects on the challenges Elizabeth has been experiencing, ‘It sounds like you are overwhelmed by all the things you need to do every day, while not having much energy. But you still keep going’. He asks, ‘Is there anything at the moment that helps you to keep going?’ Elizabeth tells him that her husband and friends are very supportive, and that having her grandchildren around makes her feel better too.

Andrew acknowledges Elizabeth’s continuous efforts to take care of her health despite not feeling very well lately. He asks about the types of support that would help her to reduce the diabetes distress. She does not answer directly, instead she continues her story – her life has not been the same since she was diagnosed with diabetes. She feels like diabetes ‘controls’ her life. Elizabeth believes she got diabetes because she is overweight, and now she wants to make up for ‘not eating healthy’ at the time she was diagnosed. But she feels like she ‘fails’ constantly with her ‘diet’.

Andrew reassures Elizabeth that it is not her fault that she developed diabetes – weight is only one of many reasons people get type 2 diabetes. Elizabeth has other family members with type 2 diabetes, so there is probably a genetic factor involved, and no-one can really say exactly how her diabetes came about. He suggests that, rather than blaming herself for getting diabetes, the most important thing now is to focus on how best to manage it. Elizabeth says she has not thought about it in that way, but that he is probably right.

Andrew summarises the different issues that Elizabeth has described to him and he also mentions the support she gets from her husband. He checks with Elizabeth which of the difficulties she has raised she would like to address first. Elizabeth tells him that her unhealthy eating is her major concern and she would like to be a bit more active; having her husband join her may motivate her to go for longer walks. They talk about how she might raise this idea with her husband.

ASSIGN

Andrew explores whether Elizabeth would like to talk to a specialist diabetes dietitian to help her find an eating plan that is more achievable and sustainable – a healthy lifestyle change, rather than a ‘diet’. Elizabeth agrees that she would like to try this and that Andrew may write her a referral to a dietitian.

ARRANGE

Elizabeth feels understood by Andrew; the conversation has helped her to feel a little bit less stressed about her diabetes. She feels positive about the plan they have made and looks forward to her appointment with the dietitian. . Andrew suggests they meet again in one month to evaluate how she is doing with her walks and how the consultation with the dietitian went. He also asks her if it would be OK to fill in the PAID at a future appointment to see if her diabetes distress has reduced. She tells him that she is happy to do so, but not too soon, because she would like to have enough time to make the changes they discussed first. They agree to revisit the PAID in a couple of months.

They continue the consultation; Andrew checks her blood pressure and they talk about her recent HbA1c and cholesterol results.

Case study

- John

- 31-year-old man, living with his partner and their daughter, and looking for employment

- Type 1 diabetes for eight years, managed using an insulin pump for the past three years

- Health professional: Sarah Jones (Diabetes Specialist Nurse)

Be AWARE

The staff at the diabetes clinic that John attends are trialling diabetes distress monitoring as a part of their routine care. The receptionist is asking all people with diabetes to complete the Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire while waiting to see their health professional. She invites John to complete the questionnaire and explains that Sarah will go through his responses with him during the consultation. She indicates that an explanation of the new protocol is included at the top of the questionnaire with the instructions. John agrees.

ASK

John hands Sarah the completed questionnaire, remarking, ‘I hate my diabetes!’ Sarah is surprised by his outburst at first but invites him to tell her a bit more about what he hates most; his response will help her to understand how she can support him.

He tells her that he has always struggled. He had hoped that using a pump would take away his frustration, but at the moment he feels worse, ‘My pump is a constant reminder that I have diabetes. And since I got it I’m having more hypos. My diabetes ruins everything’.

Sarah, who has known John since his diabetes was diagnosed, had not been aware of John’s difficulties until now. John has never mentioned a problem and, since he began using a pump, his HbA1c has always been in target. John tells Sarah that completing the questionnaire has given him a way to express his feelings about diabetes – something he has not been asked about before. John is aware that people think he is ‘on top of it’ as he keeps his stress to himself. He wants to be strong for his family but, in reality, he is really struggling. He has applied for a new job and is stressed that he may have a hypo during the interview. He doesn’t want to worry his partner or get other people involved, ‘It’s my problem’, he says, ‘I have to deal with it’.

ASSESS

Sarah casts her eye over John’s PAID responses. He has scored most of the items a ‘1’ or ‘2’ indicating that they are only a minor or moderate problem for him. Sarah notes that he has scored a few items with ‘4’, indicating they are serious problems for him. These problems were:

- not ‘accepting’ diabetes

- feeling ‘burned out’ by the constant effort needed to manage diabetes

- feeling overwhelmed by diabetes

- feeling that diabetes is taking up too much mental and physical energy every day

- worrying about low blood glucose reactions.

These responses, in combination with John’s comments, give her a good understanding of how he is feeling. His total score indicates that he is just below the threshold for severe diabetes distress. The PAID scores give Sarah a baseline level against which to compare future scores as they work to reduce his distress.

ADVISE

Sarah tells John that his questionnaire responses indicate he is experiencing diabetes distress, and she explains what this is. She reassures him that it is very common to have negative feelings about diabetes, and that the diabetes team is here to help. She tells him she would like to support him in reducing his diabetes distress, if he agrees, which he does.

ASSIST

Sarah checks whether John would like to keep using the pump. He is not sure about the long term but, for now, he would prefer not to change to injections. Sarah asks about his upcoming interview and his fear of having a hypo. They talk about practical strategies to avoid low blood glucose. John feels relieved now that he knows how to handle this. Sarah thinks John might benefit from seeking peer support, especially because he does not want to burden his partner with his distress. Sarah tells John about face-to-face and online peer support groups and asks him whether this is something he would be interested in joining. He says he will give it some thought. As there is no time to talk about the other problem areas identified in the PAID, they will take this up in the next consultation.

ARRANGE

They agree to meet again in a month to follow up about John’s distress and his experience applying the strategies they discussed today. They will also talk about how he feels about continuing with the pump. Sarah also makes a note to talk with John about not wanting to burden others with his worries, as there was no time to address this today.

Questionnaire: Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) scale

Find the PAID questionnaire, and information on how to use it on the full PDF (3MB)

Resources for health professionals

Peer-reviewed literature

- Differentiating symptoms of depression from diabetes-specific distress: relationships with self-care in type 2 diabetes. Description: An empirical paper, reporting on the results of a cross-sectional survey of people with type 2 diabetes to examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and diabetes distress. The independent relationship of depression and diabetes distress with diabetes self-care was also examined. Source: Gonzalez JS, Delahanty LM, et al. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1822-1825.

- The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision. Description: A review paper examining the differences between the definitions of depression and diabetes-specific distress as well as the differences between the approaches of measurement of depression and diabetes-specific distress. Source: Fisher L, Gonzalez JS, et al. Diabetic Medicine. 2014;31(7):764-772.

Book chapter

Problem-solving skills

This book chapter outlines the role of problem solving in diabetes self-management and the key principles of effective problem solving. The chapter was developed for health professionals who consult with people with type 1 diabetes, but the key principles of problem solving could also be incorporated (with adaptation, as necessary) into type 2 diabetes consultations. An electronic version can be downloaded from the ‘Publications’ section of the Australian Diabetes Society website.

Source: Conn J et al. Enhancing your consulting skills: supporting self-management and optimising mental health in people with type 1 diabetes. The National Diabetes Services Scheme and Australian Diabetes Society. Canberra, 2014:58-65. URL: www.diabetessociety.com.au

For people with diabetes

Select one or two resources that are most relevant and appropriate for the person. Providing the full list is more likely to overwhelm than to help.

Support

- Diabetes UK Diabetes UK is the major organisation for support, including emotional and peer support, information and research relating to diabetes. Phone: 0345 123 2399 Email: helpline@diabetes.org.uk URL: www.diabetes.org.uk

- Peer support for diabetes There are various ways of accessing peer support in the UK to share experiences and information with others living with diabetes. See Appendix B

- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) (for type 1 diabetes) Description: Pages to help with emotional support and reducing diabetes related distress for type 1 diabetes, including links to many other organisations who might help Source: JDRF URL: https://jdrf.org.uk/information-support/living-with-type-1-diabetes/health-and-wellness/emotional-wellbeing/

Information

- Diabetes distress An information leaflet to accompany this guide about diabetes distress. The leaflet includes suggestions that the person may try, in order to reduce their distress, and offers suggestions for support and additional information. The leaflet can be downloaded here (PDF, 42KB).

- Diabetes and Mood Information Prescription: Diabetes UK’s information for people with diabetes about how it can affect your mood, and some ways to cope. URL: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-02/Diabetes%20UK%20Information%20Prescription_Mood.pdf

- Diabetes UK: Emotional Wellbeing Pages providing information and sources of emotional support for reducing diabetes related distress for anyone with diabetes Source: Diabetes UK URL: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/life-with-diabetes/emotional-issues

See Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB) for our full list of references

Disclaimer: Please note you may find this information of use but please note that these pages are not updated or maintained regularly and some of this information may be out of date.