Key messages

- The term ‘eating problems’ encompasses both ‘sub-clinical’ disordered eating behaviours and full syndrome eating disorders.

- Disordered eating behaviours include food restriction, compulsive and excessive eating, and weight management practices, which are not frequent or severe enough to meet the criteria for a full syndrome eating disorder.

- Eating disorders include several diagnosable conditions (e.g. anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder), which are characterised by preoccupation with food and body weight, disordered eating behaviour, with or without compensatory weight control behaviours.

- Among people with diabetes, the full syndrome eating disorders are rare. The most common disordered eating behaviours are binge eating and insulin restriction/omission but prevalence is not well established.

- Eating problems in people with diabetes are associated with sub-optimal diabetes self- management and outcomes, overweight and obesity, and impaired psychological well-being. Eating disorders are associated with early onset of diabetes complications, and higher morbidity and mortality.

- A brief questionnaire, such as the modified SCOFF adapted for diabetes (mSCOFF), can be used as a first step screening questionnaire in clinical practice. A clinical interview is needed to confirm a full syndrome eating disorder.

- Effective management of eating problems requires a multidisciplinary team approach, addressing the eating problem and the diabetes management in parallel.

Practice points

- Ask the person directly, in a sensitive/non-judgemental way, about eating behaviours and attitudes towards food, insulin restriction/omission, and concerns about body weight/shape/ size.

- Be aware not to positively reinforce weight loss or low HbA1c when eating problems are (likely) present.

- Be aware that acute changes in HbA1c and recurring diabetic ketoacidosis could indicate insulin omission and may be an alert to the presence of an eating disorder.

How common are eating problems?

Eating disorders (anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder)

|

|

Disordered eating behaviours

|

|

What are eating problems?

Eating disorders

These comprise a group of diagnosable conditions, characterised by preoccupation with food, body weight, and shape, resulting in disturbed eating behaviours with or without disordered weight control behaviours (e.g. food restriction, excessive exercise, vomiting, medication misuse) They include:

- Anorexia nervosa: characterised by severe restriction of energy intake, resulting in abnormally low body weight for age, sex, developmental stage, and physical health; intensive fear of gaining weight or persistent behaviour interfering with weight gain; and disturbance in self-perceived weight or shape. There are two subtypes:

- restricting subtype with severe restriction of energy intake

- binge eating/purging subtype with restriction of food intake and occasional binge eating and/or purging (e.g. self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives).

- Bulimia nervosa: characterised by recurrent episodes of binge eating, at least once a week for three months, and compensatory weight control behaviours. Similar to anorexia nervosa, weight and shape play a central role in self-evaluation. In contrast to anorexia nervosa, weight is in the normal, overweight, or obese range.

- Binge eating disorder: characterised by recurrent episodes of binge eating, at least once a week for three months. People with a binge eating disorder do not engage in compensatory behaviours and are often overweight or obese.

- Other specified or unspecified feeding or eating disorders: characterised by symptoms of feeding or eating disorders causing clinically significant distress or impact on daily functioning, but that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for any of the disorders. Specified eating disorders are, for example, ‘purging disorder’ in the absence of binge eating, and night eating syndrome.

The complete diagnostic criteria for the above mentioned eating disorders can be found in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5). The criteria for eating disorders were revised in the fifth edition of the DSM. Although eating disorders develop typically during adolescence, they can develop during childhood or develop/continue in adulthood; they occur in both sexes.

Box 8.1: Prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating in adults with diabetes is not yet well established

Diabetes is likely associated with an increased risk of eating problems. However, published prevalence data are inconsistent, with some studies showing no difference in rates compared to a general population, and others reporting higher rates.

The inconsistencies are largely due to the methodology used (e.g. measures and inclusion criteria), for example:

- Data are collected typically with general eating disorder questionnaires, and the findings are not necessarily confirmed with a clinical interview or examination.

- These questionnaires tend to inflate the estimated prevalence of eating disorders and disordered eating behaviours in people with diabetes. Dietary behaviours used to manage Type 1 diabetes could be considered problematic or disordered for people without diabetes. Thus, some of the items in general eating disorder questionnaires are not appropriate for people with diabetes.

- Apart from overestimating prevalence, the questionnaires are not sensitive enough to identify diabetes-specific compensatory behaviours, such as insulin restriction/omission.

In addition, most studies have included predominantly female adolescents or young adult women and sample sizes are small.

Due to such limitations, the evidence of eating problems in adults with diabetes is limited and findings should be interpreted and generalised with caution.

Though the current evidence base is limited, it has been established that:

- the prevalence of anorexia nervosa in female adolescents and young women with diabetes is low and not more prevalent than in the general population

- people with diabetes are more likely to present with periodic overeating, binge eating and compensatory weight control behaviours with more frequent and severe behaviours likely to meet criteria for a full syndrome eating disorder such as bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder.

Future studies about eating behaviours should include men, because, as is true in women, binge eating is more common in men with Type 2 diabetes than it is in men without diabetes.

Disordered eating behaviours

These are characterised by symptoms of eating disorders but do not meet criteria for a full syndrome eating disorder. For example, binge eating episodes occurring less frequently than specified for a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder. However, if left untreated, disordered eating behaviours can develop into a full syndrome eating disorder. The following disordered eating behaviours can present in isolation or as part of an eating disorder:

- Binge eating: includes eating in a two-hour period an amount of food that most people would consider unusually large, plus a sense of loss of control when overeating. It is a symptom in all three main full syndrome eating disorders (binge eating/purging subtype of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder). It can occur in response to restrained eating (e.g. rule-based/restrictive eating), emotional cues (e.g. eating when distressed or bored), and external cues (e.g. eating in response to the sight, taste, or smell of food) (see Box 8.2).

- Compensatory weight control behaviours: include deliberate acts to compensate for weight gain following overeating or binge eating. For example, self-induced vomiting, excessive/driven exercise, medication misuse (e.g. laxatives, diuretics), omission or restriction of insulin (or other medication), fasting, or abstinence from/severe reduction in several or all food and beverages.

Intentional insulin restriction or omission

- The restriction or omission of insulin for the purposes of weight loss is unique to people with diabetes and the most common form of inappropriate compensatory weight control behaviour. Intentional insulin restriction or omission induces hyperglycaemia and loss of glucose (and calories) in the urine, enabling a person to eat with reduced concerns about gaining weight. It is sometimes referred to as ‘diabulimia’ by the media and those who are struggling, although insulin restriction is the preferred clinical term.

- Estimates of insulin omission have been reported in up to 40% of people with Type 1 diabetes. However, people omit or restrict insulin for other reasons than weight loss (e.g. fear of hypoglycaemia).

- Not all people with diabetes and an eating disorder restrict or omit insulin for weight loss. They may restrict food/calories while taking insulin as recommended and they may also compensate for overeating in other more typical eating disorder ways.

- Both general negative affect and diabetes distress substantially increase the odds of insulin restrictions.

Box 8.2: Eating styles

Certain eating styles are associated with difficulties in adjusting or maintaining healthy eating habits and weight; they may put people with diabetes at risk of developing an eating problem. For example:

- Emotional eating (in response to negative emotional states, such as anxiety, distress, and boredom): provides temporary comfort or relief from negative emotions, as a way of regulating mood. It is associated with weight gain in adults over time28 and tends to be more common in people who are overweight or obese.

- External eating (in response to food-related cues, such as the sight, smell or taste of food): accounts for approximately 55% of episodes of snacking on high fat or high sugar foods in people who are overweight or obese.

Emotional and external eating may increase the likelihood of snacking on high fat or high sugar foods, higher energy intake, overeating and binge eating, and night-time snacking.

- Restrained eating (attempted restriction of food intake, similar to being on a diet, for the purpose of weight loss or maintenance): may be an adaptive strategy to manage diet and weight for people with diabetes, but there is evidence that it may be associated with sub- optimal HbA1c.

As a first step approach, a dietitian with experience in diabetes is best placed to support people with diabetes whose eating styles hinder maintaining a healthy diet and weight.

Eating problems in people with diabetes

There are indications that diabetes itself could be a risk factor for developing or exacerbating eating problems due to:

- Behavioural changes: the emphasis on dietary management (type, quantity and quality of foods eaten, as well as timing of food intake), can lead to dietary restraint (restriction of food intake and adoption of dietary rules), which is associated with an increased risk of disordered eating and eating disorders.

-

Physical changes: people with Type 1 diabetes commonly experience weight loss prior to diagnosis, and weight gain following insulin treatment, whilst overweight and obesity is associated with the diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes. Increasing body weight is associated with body dissatisfaction and concerns about body shape,16which in turn increases the risk of developing disordered eating.

-

Psychological changes: the psychological burden of diabetes management can lead to low mood and psychological distress, which are associated with eating problems. Between 55-98% of people with an eating disorder report a concurrent mood or anxiety disorder.

-

Physiological changes: in Type 1 diabetes, beta cells are destroyed and unable to secrete insulin and amylin, whilst beta cell functioning declines and insulin resistance worsens over time in people with Type 2 diabetes. These changes in insulin secretion and insulin resistance lead to dysregulation of appetite and satiety and disruption of long-term weight regulation in people with diabetes.

It may be difficult to distinguish disordered eating behaviours from self-care behaviours required for diabetes management, both include weighing foods, counting calories and carbohydrates, and avoiding certain foods. Signs of disordered eating behaviours may remain undetected if mistaken for ‘normal’ diabetes management behaviours.

Diabetes self-management behaviours may become disordered when they are:

- used inappropriately to achieve rapid weight loss (or to maintain an inappropriate goal weight), and

- carried to excess or impose rigid rules on the person’s lifestyle.

As a result, these inappropriate diabetes self- management behaviours can interfere with activities of daily living, pose a significant health risk, and impair the person’s emotional well-being.

The combination of diabetes and an eating disorder adds to the complexity of the treatment. Therefore, early identification of the signs of disordered eating and body dissatisfaction is warranted to prevent full syndrome eating disorders. As evidence has shown,3eating disorders usually develop early in life, and as such, screening should start during adolescence.

Eating problems in people with Type 1 diabetes are associated with:

- blood glucose levels above recommended targets

- impaired mental health

Eating disorders in people with Type 1 diabetes, especially when insulin restriction/omission is involved, are associated with:

- earlier onset of and increased risk of microvascular complications (e.g. retinopathy, neuropathy)

- more frequent episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis and diabetes-related hospital admissions

- up to three times greater risk of mortality over a 6-10 year period.

Eating problems in people with Type 2 diabetes have not yet been widely investigated, but available research shows that they are associated with:

- overweight and obesity

- lower self-efficacy for diet and exercise self-management

- sub-optimal dietary and glucose levels, but not HbA1c

- not taking medications as recommended

- impaired mental health44 and quality of life.

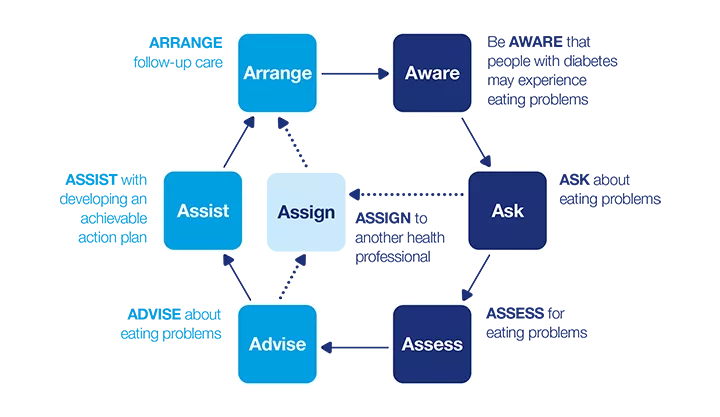

7 As model: Eating problems

This dynamic model describes a seven-step process that can be applied in clinical practice. The model consists of two phases:

- How can I identify eating problems?

- How can I support a person with an eating problem?

Apply the model flexibly as part of a person-centred approach to care.

How can I identify eating problems?

Be AWARE

The following signs (general and diabetes-specific) may indicate a full syndrome eating disorder or be part of disordered eating behaviour:

- frequent and restrictive dieting and beliefs about food being ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, ‘good’ or ‘bad’

- preoccupation and/or dissatisfaction with body shape, size, or weight (signs may be: reluctance having their weight taken, negative self-statements about weight and/or shape)

- unexplained weight loss or gain

- sub-optimal diabetes self-management, including: less frequent or no blood glucose monitoring (i.e. not presenting blood glucose readings at consultation), frequent changes to insulin regimen, restriction/omission of insulin, overdosing of insulin (to compensate for binges), missed clinical appointments

- sub-optimal diabetes outcomes, including: unexplained high or low HbA1c (a sign of food restriction without insulin omission); acute change in HbA1c (a sign of the onset of an acute eating disorder, often with insulin omission); erratic fluctuating blood glucose levels; recurrent hypoglycaemia (with binge eating and self-induced vomiting); recurrent diabetic ketoacidosis and diabetes-related hospitalisations; and early development of microvascular complications

- depression, distress, and anxiety

- personality traits such as perfectionism, and obsessiveness

- low self-esteem

- overall impaired psychosocial functioning (e.g. at school, work, or in relationships)

- concern expressed by a third party (e.g. partner or parent)

- dysfunctional family dynamic

- physical signs as a consequence of an eating disorder (e.g. calluses on the hands, oedema, dental problems).

Not all of the above mentioned signs automatically indicate an eating problem as some may relate to other underlying psychosocial problems.

Two classification systems are commonly used for diagnosing eating disorders: DSM-514 and ICD-10.13 Consult these for a full list of symptoms and the specific diagnostic criteria for each type of eating disorder.

Look for signs of eating problems in men, not only in women.

Disordered eating behaviours can be hidden, and the signs of eating problems can be subtle and difficult to determine from observation alone.

If any of the markers of eating problems are present, further enquiry is warranted.

ASK

When you have noticed signs of eating problems (see AWARE) or the person raises a problem, ask directly, in an empathetic and non-judgemental way, about eating and weight management behaviours, as well as concerns about body weight/shape/size.

Option 1: Ask open-ended questions

You may find it helpful to lead in to questions with a comment about the focus of food and carbohydrate counting in diabetes management, which could cause concerns or anxiety about weight and food intake. For example:

- 'Women (men) with diabetes are sometimes concerned about their weight or shape. How do you feel about your weight or body shape?’

- ‘People sometimes feel that food and eating are a difficult part of managing diabetes. Do you find it hard to control what and how much you eat? Can you tell me a bit more about it? How often does this occur?’

Explore the underlying reasons for disordered eating behaviours, for example:

- ‘Could you tell me a bit more about the recent changes in your eating patterns?’

- ‘Have you noticed any changes in your life that could be the reason for the changes in your eating patterns?’

Explore the person’s beliefs, behaviours, and concerns about food, eating, body image, and weight. Enquire further to help identify the specific underlying causes of the problem. You will find that not all of the underlying causes relate to eating problems (e.g. social/family changes/stress or other mental health issues may also contribute).

Explore any changes to their diabetes management plan or blood glucose levels, and difficulties encountered with diabetes management.

- ‘Some people with diabetes find it difficult to keep up with their insulin injections/boluses. How is this going for you? Do you sometimes miss or skip your insulin?’ If the answer is yes, ‘Could you tell me about the reasons you miss [skip] insulin’ or ‘Do you ever adjust your insulin to influence your weight?’ Explore how often this occurs, and the person’s beliefs and feelings about medication restriction/omission.

- ‘Your HbA1c has been going up over the last couple of months and you mentioned you have gained/lost weight. How do you feel about this? Have you thought about what may be going on?’

There is controversy about whether asking about insulin omission could unintentionally trigger inappropriate weight loss behaviours in people with Type 1 or 2 diabetes who use insulin therapy. Health professionals may feel uncomfortable to ask about insulin omission/restriction for the same reason. Whether or not this conversation can take place comes back to the respectful and non-judgemental relationship between the health professional and the person with diabetes, the way the questions are phrased and how the person with diabetes’ responses are addressed during the conversation. Maladaptive behaviours such as insulin omission often go unrecognised for a long time, perhaps because this conversation is not taking place. The consequences of insulin omission are serious, for the physical and mental health of the person. Be aware that people with diabetes have other ways of learning about these behaviours (e.g. pro-eating disorder websites or social media). Not talking about it will not prevent people with diabetes from omitting insulin.

People may restrict/omit insulin for weight loss purposes after they have overtreated a hypoglycaemic episode. You might like to use following questions related to hypoglycaemia:

- ‘When you think your blood glucose is low (or when you have a hypo), do you eat foods that you do not normally allow yourself to have (e.g., chocolate, chips)?’

- ‘When you think your blood glucose is low, do you continue to eat until you feel better, rather than waiting 15 minutes or so between servings to see if your symptoms improve?’

- ‘Do you feel like you lose control over your eating when your blood glucose is low?’

If the person with diabetes responds ‘yes’ to any question, ask how often it occurs.

Some people with diabetes may feel relieved that you have asked about their eating behaviours/problems, for example, because they feel alone and hopeless about overcoming the problem. Other people may be reluctant to talk about their eating problem because they:

- have had a negative experience with a health professional

- feel ashamed or guilty about their eating habits or weight/body

- fear being judged

- find their current habits rewarding (e.g. they might have lost weight or received compliments from others about their appearance)

- deny the seriousness of their symptoms and condition.

Therefore, creating a respectful, non-judgemental, empathetic relationship will create a safe environment for a person with an eating problem to open up and ask for support.

If the person is not ready to talk about their eating problem now, or with you, consider giving them an information leaflet about disordered eating with reference to online or telephone support.

When needed and if possible, speak to other people (e.g. their partner, family members, or other health professionals) to gain information about the person’s eating behaviour. Gain consent from the person with diabetes before having this conversation.

Option 2: Use a brief questionnaire

Currently, there are limited choices for eating problem questionnaires that are validated in people with diabetes.

However, the SCOFF (a screening questionnaire for eating disorders) was recently modified for people with diabetes (mSCOFF) and trialled with a small sample of adolescent girls with Type 1 diabetes.

The mSCOFF consists of five questions:

|

Do you make yourself sick (vomit) because you feel uncomfortably full? |

Yes | No |

|

Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat? |

Yes | No |

|

Have you recently lost more than six kilograms in a three-month period? |

Yes | No |

|

Do you believe yourself to be fat when others say you are too thin? |

Yes | No |

|

Do you ever take less insulin than you should? |

Yes | No |

© American Diabetes Association 2014. Reproduced with permission. Permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Centre, Inc.

A printable version of the mSCOFF is available on the full Emotional health and diabetes PDF (3MB)

Next steps: ASSESS or ASSIGN?

If AWARE or ASK has indicated disordered eating, a comprehensive clinical assessment is required to diagnose the type and severity of the eating problem. This includes both a clinical interview and clinical examination.

If a comprehensive clinical assessment is outside your expertise, you will need to refer the person to a health professional with expertise in eating disorders. These specialists are best placed to conduct comprehensive clinical assessments to diagnose disordered eating behaviours/eating disorders.

Instead of administering this as a questionnaire, you could integrate these questions into your conversation.

If the person answers ‘yes’ to one or more mSCOFF questions, further assessment for eating problems is warranted.

If the person answers ‘yes’ to the last item, explore the reasons for taking less insulin as these may not be related to weight loss purposes.

The Diabetes Eating Problem Survey – Revised (DEPS-R) is a 16-item diabetes-specific questionnaire, which has been validated, but only in youth and adolescents with Type 1 diabetes.

If disordered eating behaviours are identified through the conversation or the person’s mSCOFF responses, further assessment is recommended to better understand the person’s specific issues and severity of the eating problem. From a clinical perspective, any problematic eating behaviour requires further attention, as it has a significant impact on the person’s short- and long-term diabetes and health outcomes and can intensify over time. At this stage, it is advisable to ask whether they have a current diagnosis of an eating disorder and, if so, whether and how it is being treated.

ASSESS

A comprehensive clinical assessment includes both a clinical interview and clinical examination. For a full description of how to diagnose anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder, consult NICE Clinical Guidelines NG69 and recommendations specifically for type 1 diabetes in Goebel-Fabbri.

Clinical interview

A clinical interview assesses:

- any physical symptoms (e.g. gastrointestinal, cognitive, and sleep problems, menstrual disturbances)

- the history of the current problem

- the history of any previous eating disorders (and treatment)

- eating habits and beliefs, concerns about and importance of weight and shape

- personality traits (e.g. perfectionism, obsessiveness)

- any co-existing mental health issues (e.g. anxiety, depression)

- current risk and previous attempts at self-harm and suicide (see Box 6.3).

Clinical examination

A clinical examination checks the person’s medical history and complications, current health status, general physical examination, and blood tests (e.g. HbA1c, ketones, potassium, sodium). The clinical examination is also able to exclude any other conditions that could cause changes in weight or appetite.

- A list of the required medical checks to assess for eating disorders can be found in the above mentioned guidelines/recommendations.

- Blood tests and/or physical symptoms do not always confirm an eating disorder even when one is present.

- Consider whether there is an acute risk for the person

Additional considerations

- If there are no signs of disordered eating or an eating disorder, but you or the person with diabetes still have concerns about/dissatisfaction with their weight/shape/eating behaviours: consider assessing their eating styles (see Box 8.2) or body dissatisfaction. Referral to a diabetes specialist dietitian and/or psychologist may be the best option.

- Consider whether there are co-existing mental health problems, for example, mood disorders and anxiety disorders, as these are associated with changes to appetite, physical activity, medication adherence, and self-esteem; these changes are also found in disordered eating behaviours and eating disorders. Depression and disordered eating behaviours commonly occur together, suggesting either a shared vulnerability to both or that experiencing one of these problems may increase the risk of developing the other.

How can I support a person with an eating problem?

ADVISE

Now that you have identified signs of an eating problem:

- Acknowledge the high focus on food in the management of diabetes and the difficulties it may cause for a person with diabetes.

- Explain that, based on your conversation or the mSCOFF scores (if used), they may have an eating problem, but that this needs to be confirmed with a clinical interview and clinical examination.

- Elicit feedback from the person about their mSCOFF scores or signs (i.e. whether they have considered they may have an eating problem).

- Describe the differences between disordered eating behaviours and eating disorders.

- Advise that untreated eating problems can impact negatively on their life overall, as well as on their diabetes management/outcomes and general health.

- In the event of insulin omission, advise them about the risk for early onset of long-term complications (e.g. retinopathy, neuropathy).

- Advise that support is available, that eating problems can be managed effectively, and that early intervention (before the eating problem is well established) is important to prevent long-term health problems.

- Recognise that identification and advice alone are not enough; explain that treatment will be necessary and can help to improve their life overall, as well as their diabetes management.

- Offer the person opportunities to ask questions.

- Check how the person is feeling before ending the consultation, as the information you have provided may have an emotional impact on the person.

- Make a joint plan about the ‘next steps’ (e.g. what needs to be achieved to address the eating problem and who will support them).

To begin the conversation, you may say something like this:

- ‘From what you have told me, it sounds like you are having some concerns about your [eating habits/weight/body image/insulin use]. These concerns are not uncommon in people with diabetes. If you are OK with this, perhaps we could talk a bit more about what is going on and see what is needed to reduce your concerns.’

- Continue: ‘After listening to you and seeing your blood test results, I wonder if you might be struggling with disordered eating or an eating disorder. Has this crossed your mind? Has anyone else suggested they are concerned about your [health/eating habits/weight?]’

Next steps: ASSIST or ASSIGN?

Support and treatment for eating problems requires a collaborative care approach. The decision about which health professionals are a part of the multidisciplinary team will depend largely on the severity and type of the eating problem, and who has the relevant expertise to support the person.

Disordered eating (behaviours): The general practitioner (GP) involved in the person’s diabetes management has a key role in the early detection of disordered eating behaviours and/or body dissatisfaction. If the person is experiencing disordered eating, GPs are best placed to coordinate collaborative care with other health professionals, such as a dietitian and a psychologist (see Box 8.3). Because diabetes adds to the complexity of an eating problem, input/support from a diabetes health professional (e.g. diabetologist or credentialled diabetes nurse educator with diabetes specialist) for adjusting the diabetes treatment plan may also be required. Thus, if you are not the person’s GP, you will need to ASSIGN the person to their GP, but you may also play a role in the ASSIST as a part of the multidisciplinary team.

Full syndrome eating disorder: Collaborative care integrating a multidisciplinary team with expertise in eating disorders (and including medical, dietetic, and psychological/ psychiatric intervention) is the standard approach for support and treatment of eating disorders (see Box 8.3). Inclusion of a specialist in diabetes in the team is also essential. Therefore, you will need to collaborate with other specialists to ASSIST, and ASSIGN the person to health professionals for specialist care outside of your expertise.

Consider:

- Options for support and treatment vary according to geography and include outpatient, day programme and inpatient treatment in severe cases. Where to ASSIGN will depend on multiple factors (e.g. availability of services, type and severity of the eating disorder, geography).

- The Australian and New Zealand guidelines recommend treatment in the least restrictive context possible, utilising a stepped care approach. The safety of the person is the first priority; therefore, inpatient treatment may be required depending on the severity of the eating disorder.

- Involuntary assessment and treatment may be required if the person has impaired decision-making capacity and cannot or will not consent to life-preserving intervention.

Box 8.3: The collaborative care team

The multi-disciplinary collaborative care team for eating problems must include:

- A medical practitioner (either a GP or diabetologist) to obtain the person’s medical history and arrange the medical checks required to diagnose/treat eating problems. They can also assist with the general medical and diabetes- specific aspects of care during the treatment/ therapy of the eating problem. The GP is often also well placed to co-ordinate the collaborative care team and to take on long-term follow-up of the person.

- A mental health professional, preferably with expertise in eating disorders and diabetes (either a diabetes specialist (psychologist or psychiatrist) to provide psychotherapy and address the psychological and social aspects of the eating disorder, as well as any co-existing mental health problems (e.g. mood or anxiety disorders).

- A diabetes specialist dietitian, to assist with developing flexible and structured eating plans appropriate for people with diabetes and medical nutrition therapy goals appropriate for people with both diabetes and an eating disorder. Also, a dietitian can support people with diabetes to have strategies in place to effectively deal with cues to overeating (e.g. negative emotions, low blood glucose) when they arise.

- A diabetes specialist nurse to provide diabetes-specific care throughout treatment.

Ideally, all members of the collaborative care team will have knowledge, skills, and experience in both eating disorders and diabetes; however, it may be unlikely everyone in the team will have this combined expertise. A health professional with experience in eating disorders only, can be trained by and collaborate closely with diabetes experts.

Keep consistency in messages and treatment goals, philosophy, and delivery by facilitating regular communication between all team members. This will also help to ensure smooth transitions between services.

ASSIST

Evidence for the management of eating disorders in combination with diabetes is very limited. Thus, in practice, general eating disorder treatments are applied to address the needs of people who are living with both conditions.

Once disordered eating behaviour(s) or an eating disorder has been confirmed by a comprehensive clinical assessment, and if you believe that you can assist the person as a part of the multidisciplinary collaborative care team (see Box 8.3):

- Provide information about the specific eating problem that was identified during the comprehensive clinical assessment, and its likely impact on diabetes management/outcomes and general health.

- Explain and discuss treatment options with the person to enable them to make a well-informed decision. This will help them to engage with the treatment/therapy, which will likely be a combination of:

- an adapted diabetes management and dietary plan: with more flexible and realistic blood glucose targets, and with less focus on weight loss or strict dietary plans between services.

- psychological therapies: for example, family-based therapy (if the person is still living with family), enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) or interpersonal therapy (IPT). These aim to address -unhelpful thoughts, emotions, and behaviours (CBT-E) or problems in relationships (IPT)

- pharmacological treatments.

- Assist the person to access appropriate support and treatment (e.g. if you are a GP: establish a collaborative care team, including referral to a relevant health professional who can provide psychological therapy).

- Explain that a collaborative approach is needed, and which health professionals will be part of the team (see Box 8.3).

- Agree on an action plan together and set achievable goals for managing their diabetes and eating problem.

- Make sure the person is comfortable with this approach.

- At the end of the conversation, consider giving them information to read at home. At the bottom of this page, there are several resources that may be helpful for a person with diabetes who is experiencing eating problems. Select one or two of these that are most relevant for the person; it is best not to overwhelm them with too much information.

There may be a need to work with the family and to liaise with schools and other agencies if the person with diabetes is still living at home or attending school.

Eating disorder treatment recommendations specific to Type 1 diabetes can be found in the NICE guidelines and Goebel-Fabbri.

ASSIGN

If the person is at immediate risk: they will need to go to hospital. For example, people with recurrent episodes of diabetes ketoacidosis, cardiac arrhythmias, hypothermia, hypotension, electrolyte abnormalities, or if the person has stopped taking insulin, should be referred to specialist inpatient services or taken to the nearest hospital for treatment.

If the person is not at immediate risk: refer them to specialist eating disorder outpatient services or day programmes. It is likely that the staff of the specialist eating disorder in- or outpatient services do not have expertise in diabetes management or the unique aspects of eating disorders in diabetes. You will need to keep regular, close contact with the treatment team to help ensure that the person receives appropriate care.

ARRANGE

As an eating disorder requires a multidisciplinary approach, the follow-up plan will depend on the agreed-upon course of action for treatment:

- If you are part of the multidisciplinary team: continue to monitor the person’s progress (e.g. blood test assessments, diabetes complications). Medical treatments, nutrition plans, and diabetes self-management goals will need to be adjusted regularly throughout the treatment. The management of an eating disorder will require regular follow-up visits and/or extended consultations to evaluate progress and the action plans. Telephone/video conferencing may be a practical and useful way to provide support in addition to face-to-face appointments.

- If you are not part of the multidisciplinary team:enquire at each consultation about the person’s progress (e.g. have they engaged with the planned treatment?).

Case study

- Sarah

- 59-year-old woman living alone

- Type 2 diabetes, managed with diet and exercise; BMI=32

- Health professional: Dr Lydia Morris (GP)

Be AWARE

When Sarah arrives for her routine check-up, Lydia notices that she has put on weight. When Lydia asks how she has been since she last saw her and how her diabetes management is going, Sarah informs Lydia that she:

- has been trying really hard to lose weight but her efforts do not payoff

- has gained five kilograms over the past few months

- Feels down about her weight and embarrassed about her body.

ASK

Using open-ended questions, Lydia explores Sarah’s feelings about her weight and her current eating patterns. Sarah confides that she:

- has always struggled with her weight and that she is currently at her highest weight ever

- eats little throughout the day and then overeats most nights

- overeats when she's lonely or bored.

Lydia is concerned about Sarah’s weight gain and overeating and the impact it might have on her diabetes in the long-term. Lydia informs Sarah that she would like to ask her some further questions about her eating, body image, and weight. Lydia goes through the mSCOFF with Sarah. Sarah replies ‘yes’ to two items: ‘Do you make yourself sick because you feel uncomfortably full?’ and ‘Do you worry you have lost control over how much you eat?’. Sarah’s responses suggest that she may be experiencing eating problems, most likely, disordered eating. Sarah confides that she feels distressed about her overeating and resulting weight gain, and has a tendency to restrict her food intake, but also to overeat at the end of the day and in response to negative emotions.

ADVISE

Lydia explains the mSCOFF results to Sarah and reassures Sarah that emotional eating can be successfully modified. Given Sarah’s tendency to set rigid rules for her diet that she often breaks, resulting in her feeling ‘like a failure’ and eating more to feel better, Lydia and Sarah agree that she needs to develop a more flexible approach to her diet and more effective ways of dealing with her negative emotions. As such, support from both a dietitian and a psychologist (specialising in eating disorders) is the preferred approach.

ASSIGN

Lydia explains what Sarah can expect of each of the health professionals (e.g. psychologist to undertake further assessment and support Sarah with her negative emotions). Lydia refers Sarah to a psychologist and a dietitian (preferably with an understanding of diabetes).

ARRANGE

Despite her concerns, Lydia is satisfied that Sarah is not at immediate risk. She asks Sarah to make a follow-up appointment in one month to update her on her progress with the dietitian and psychologist. She checks whether Sarah had any other agendas for this consultation and continues with the routine check-up.

‘My relationship with food now... it’s hard... sometimes I just feel like I don’t enjoy my food, because I’ve got to think so hard about what goes into my mouth, and then I’ve got everyone around me telling me what to do. Like today I haven’t eaten... and I’ve been trying to keep on top of my insulin which I haven’t been doing the best...’ - Person with Type 2 diabetes

Case Study

- Eliza

- 25-year-old woman, lives at home with her family

- Type 1 diabetes (14 years), managed with insulin pump, BMI=19

- Health professional: Dr Mark Haddad (Diabetologist)

Be AWARE

Mark has been seeing Eliza since she was first diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at age 11. Eliza has been managing her diabetes very well until recently; in the past six months, she has been hospitalised twice for diabetic ketoacidosis. Additionally, her most recent HbA1c was 116 mmol/mol (12.8%), while previously it ranged between 53 and 64 mmol/mol (7-8%). Mark is concerned that Eliza is struggling to keep engaged with her diabetes management. He wonders what may have changed over the past six months for Eliza. Eliza has her next appointment with Mark.

ASK

Mark informs Eliza about her most recent HbA1c result. He asks how she feels about this result, whether she expected it, and about her recent hospitalisations.

Mark notices that Eliza’s appearance and demeanour seem different than usual, and that she:

- has lost weight since he last saw her

- appears uncomfortable and does not look at him much during the consultation

- seems ‘flat’ and does not seem to have much energy

- answers his questions with few words.

Mark asks Eliza what she thinks may be causing the higher HbA1c. First she says she has ‘no idea’, but then confides that she is ‘not eating well’ and that she sometimes ‘forgets’ to bolus. Based on what Mark has observed and Eliza’s recent hospitalisations, Mark is concerned that Eliza might be at an early stage of an eating disorder, and is omitting insulin for weight loss purposes (she has missing data in her pump downloads).

Mark informs Eliza that people with diabetes sometimes struggle with their eating, and that it can have a negative impact on diabetes outcomes and general health. He asks Eliza if she will answer some questions to help him better understand her eating patterns. Eliza agrees and Marks uses the items in the mSCOFF to guide a conversation about Eliza’s eating behaviour and body image. Eliza indicates that she:

- has lost about around 6kg in the past three months due to restricting what and how much she eats

- often feels unhappy with her weight and shape, despite her recent weight loss

- misses insulin when she feels like she has eaten too much

- started missing insulin eight months ago, at first sporadically, but now on most days

- continues to inject long-acting insulin at night

- is avoiding seeing her friends, as she feels unhappy with her weight.

Mark takes time to ask additional questions about what may have caused these changes.

ADVISE

Based on their conversation, Mark is concerned for Eliza. He explains to her that:

- the things she has described suggest she may have an eating problem, possibly she is at an early stage of an eating disorder

- as she has already experienced, the eating problems and missing insulin can have a negative impact on her diabetes management and outcomes (e.g. recent diabetic ketoacidosis episodes) and other areas of her life (e.g. not wanting to see friends, feeling ‘obsessed’ with weight and eating)

- not taking all the required insulin puts her at risk of developing complications

- with treatment, eating problems can be resolved

- it is important to address eating problems as early as possible, to prevent them evolving into an eating disorder.

Mark will continue to support her with her diabetes management (and to work with her in overcoming the insulin omission) but he also suggests seeing other health professionals for support with the eating problems.

ASSIGN

Given Eliza’s recent hospitalisations for diabetic ketoacidosis and her ongoing insulin omission, Mark suggests that Eliza attends a specialist outpatient clinic for eating disorders to see a psychologist and a dietitian (preferably with an understanding of diabetes). Although initially Eliza is hesitant to be referred to other health professionals, she understands that her future health is at risk. She agrees for Mark to contact the outpatient clinic to arrange for and make a referral.

ARRANGE

Mark and Eliza agree to see each other again in two weeks. Eliza gives Mark permission to stay in contact with the specialists in the clinic (for collaborative care). At the next consultation, Mark and Eliza will discuss whether her diabetes management plan needs adapting while she is seeing the specialists in the outpatient clinic.

Resources

For health professionals

Peer-reviewed literature

- Disordered eating behaviour in individuals with diabetes: Importance of context, evaluation, and classification This review reports on the prevalence of disordered eating, available assessment measures and the impact of insulin on weight

Source: Young-Hyman D & Davis C. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:683-689.

- Outpatient management of eating disorders in Type 1 diabetes. This paper focuses on outpatient strategies for the management of eating disorders and lists treatment recommendations specifically for people with Type 1 diabetes.

Source: Goebel-Fabbri AE, Uplinger N. et al. Diabetes Spectrum. 2009;22:147-152.

- Comorbid diabetes and eating disorders in adult patients. This overview paper describes procedures for assessment and interventions for people with Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes,

Source: Gagnon C, Aime A. et al. The Diabetes Educator. 2012;38:537-542.

Resources

- InsideOut Institute. This website contains information for health professionals including links to guidelines, information on prevention, assessment and treatment, factsheets, and case studies. Look for the ‘Health Professionals’ section of the website

- Anorexia & Bulimia Care (In partnership with the Royal College of General Practitioners). Online training course in Eating Disorders for GPs and primary healthcare professionals.

- A guide to risk assessment for type 1 diabetes and disordered eating (T1DE); medical, psychiatric, psychological and psychosocial considerations by the Wessex ComPASSION Team.

For people with diabetes

Select one or two resources that are most relevant and appropriate for the person.

Providing the full list is more likely to overwhelm than to help.

Support

Diabetes UK: Facts and further information about insulin omission (‘diabulimia’) and how to access the Helpline, with dedicated, trained counsellors to help.

Phone: 0345 123 2399

website: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/guide-to-diabetes/life-with-diabetes/diabulimia

BEAT Eating Disorders: Provides support for people (with or without diabetes) struggling with any type of eating disorder. Support groups, helplines and information leaflets.

Phone Helpline: 0808 801 0677

website: https://www.beateatingdisorders.org.uk/

FREED: FREED is First Episode Rapid Early Intervention for Eating Disorders. It is a service for 16 to 25-year-olds who have had an eating disorder for three years or less.

website: https://freedfromed.co.uk/

Anorexia and Bulimia Care

Providing information and support for non-diabetes specific eating disorders. Support for family and carers.

Helpline 03000 11 12 13

URL: http://www.anorexiabulimiacare.org.uk

The Eating Blueprint

Information and support for individuals struggling with external/non-hunger/binge eating difficulties. Offers psychological strategies to support weight management. Free online Starter Pack available from the website.

website: http://eatingblueprint.com/

Information

Eating Disorders: An NHS Self-Help Guide

A booklet on ‘Eating Disorders’ that can be freely downloaded from Northumberland Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust.

website: https://web.ntw.nhs.uk/selfhelp/

Disordered eating /diabulimia and diabetes

An area of the T1 Resources website with information and video

Source: T1 Resources

website: https://www.t1resources.uk/resources/item/disordered-eating-diabulimia-and-diabetes-infographic/

Books

- Getting Better Bit(e) by Bit(e) (2007, Ulrike Schmidt and Janet Treasure, Routledge, UK): A self-help ‘Survival Kit’ for people struggling with bulimia and binge eating disorders.

- Diabetes and Wellbeing: Managing psychological and Emotional Challenges in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes (2013, Dr Jen Nash, John Wiley and Sons, UK): Written by Dr Jen Nash, Clinical Psychologist who lives with Type 1 diabetes, with a chapter titled ‘Managing Food, Weight and Emotions’.

See Diabetes and emotional health PDF (3MB) for our full list of references

Disclaimer: You may find this information of use but please note that these pages are not updated or maintained regularly and some of this information may be out of date. These pages were created in 2019 and all information was correct at time of creation.